Since its birth, nuclear power has been a target of environmental activism. To be fair, when nuclear power goes wrong, it goes wrong in a bad way. Take a look at what’s happening in Japan right now. Friday’s tsumani damaged the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, and several of its reactors have experienced partial meltdowns. Radiation from the nuclear reactions has been released into the surrounding environment, and could endanger public health in the immediate area, causing cancer and birth defects.

Nuclear disasters are horrifying, and this is by no means the worst that has happened. However, nuclear isn’t the only form of energy that experiences periodic disasters. In fact, over the past century, hydroelectric disasters have killed more people than all other forms of energy disasters combined.

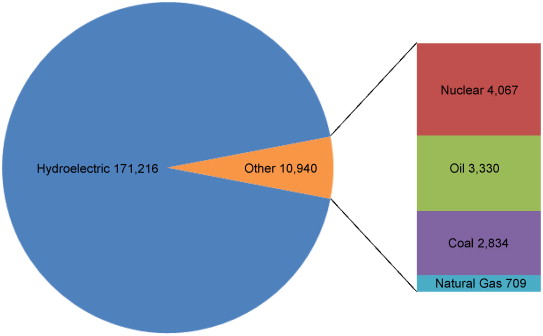

(Sovacool et al, 2008, Fig. 1).

So why do we worry so much more about nuclear power disasters? Is it because the idea of the resulting radiation is more disturbing than the prospect of a dam breaking, even if it’s far less common?

However, an energy source can kill people without a large-scale disaster occurring. Let’s look at fossil fuels. Think of all the miners killed by coal accidents, all the people killed by smog inhalation or exposure to toxic chemicals (such as heavy metals) that are present in fossil fuels, deaths due to gas leaks, civilians killed by wars over oil, and so on. It’s difficult to quantify these numbers, because fossil fuels have been in use for centuries, but they clearly exceed the 4,000 or so deaths due to nuclear power accidents (as well as any other deaths due to nuclear power, such as uranium mining).

We must also look at the deaths due to climate change, which fossil fuel burning has induced. The World Health Organization estimates that over 150 000 people died as a result of climate change in 2000 alone. This annual rate will increase as the warming progresses. If we don’t step away from fossil fuels in time, they could lead to a devastating amount of death and suffering.

Fossil fuels are silent, passive, indirect killers which end up being far more destructive to human life than nuclear power. However, much of the public remains opposed to nuclear energy, and I believe this is a case of “letting perfect be the enemy of good”. I feel that we hold nuclear power to an impossible standard, that we expect it to be perfect. It’s certainly not perfect, but it’s far better than the existing system, which desperately needs to be replaced.

There are also exciting developments in nuclear technology that could make it safer and more efficient. In his recent book, top climatologist James Hansen described “fast reactors“, which are a vast improvement over the previous generations of nuclear reactors. It’s also possible to use uranium-238 as fuel, which makes up 99.3% of all natural uranium, and is usually thrown away as nuclear waste because reactors aren’t equipped to use it. Another alternative is to use thorium, a safer and more common element. If we pursue these technologies, the major downsides of nuclear power – safety and waste concerns – could diminish substantially.

Renewable sources of energy, such as solar, wind, and geothermal, are safer than nuclear power, and also have a lower carbon footprint per kWh (Sovacool, 2008b, Table 8). They are clearly the ideal choice in the long run, but they can’t solve the problem completely, at least not yet. Cost is a barrier, as is the problem of storing and transporting the electricity they generate. Maybe a few decades down the line smart grids will become a reality, and we will be able to have an energy economy that is fully renewable. If we wait for that perfect situation before doing anything, though, we will overshoot and cause far more climate change than we can deal with.

I don’t know if I would describe myself as “pro-nuclear”, but I am definitely “anti-fossil-fuel”. I am aware of the risks nuclear power poses, and feel that, from a risk management perspective, it is still preferable to coal and oil by a long shot. Solving climate change will require a multi-faceted energy economy, and it would be foolish to rule out one viable option simply because it isn’t perfect.

I have always held that IF you want to significantly reduce the carbon footprint and still have the kind of abundant energy that our nations demand, then you would have to look to nuclear as the alternative to fossil fuels and use hydrogen for transportation. It would take at least a generation to make the transition, but it would make a significant impact.

[citations needed re: how much energy from fossil fuels could be replaced by solar and wind]

The point I would throw out for discussion is how do we balance the “cost” even in human lives of the various power sources with the “benefits” especially in human lives that are provided by that same power?

John

I am basing that assumption on the struggles we are having here in California to even get 30% of our electricity from ALL renewables, not just wind and solar.

When you try to bring them on in these amounts you have costs that are difficult for average rate payers to bear, technology challenges that could be solved in the future and resistance because of the environmental problems with placement and distribution lines.

John

I think that is an ‘American’ issue based on the fact that the US population has been used to low prices for decades compared to the vast majority of countries.

In most countries people pay higher prices for energy. The issue is really a case of where you spend money. If energy is more expensive, then you either reduce the amount you use by being more efficient (smaller cars, homes etc like the rest of the planet) or you have less to spend elsewhere.

I think there is no doubt this incident is second after Chernobyl, with Japanese authorities under estimating the severity. Given Chernobyl was level 7 and Three Mile Island was 5. Logically this is 6.

But maybe the ratings need to be reviewed since they don’t take into account the psychological effect that multiple break downs at multi-reactor sites have.

Authorities need to review the logic of placing so many reactors on one site and the stress on the work force such sites have.

The other point is that the idea that consumer demand should be met, needs to be revised. Unfortunately there is plenty of profit in meeting demand but little profit in reducing demand. That fallacy of economics has to be addressed for the sake of long term sustainability.

Warmcast,

I don’t think you can look at “profit” as only a one way street.

As long as utilities have to charge for the power they supply, then the “profit” motive that reduces consumption is seen from the point of the end user: If I use less, then I pay less.

John

Interesting piece.

I would be a bit careful with the first Sovacool paper… he states the victim count of Chernobyl as ‘at least 4056 people’ (and then uses this as his total number). A little sloppy… the 4000 figure comes from epidemiology by UNSCEAR*, and I would say, believe only the first decimal, if that. And I don’t think they meant it as an ‘at least’ number! Then, to this he adds the much more precise number 56, on which I have dark suspicions where he gets it from :-(

*UNSCEAR is here

http://www.unscear.org/unscear/en/chernobyl.html

but the 4000 figure is surprisingly hard to find, though widely quoted… I found this

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2005/pr38/en/index.html

Thank you, Kate, for offering some perspective. When I look at mountain top removal for coal and oil spills it is clear that humans are not the only casualties of fossil fuels.

I would be careful with judging the Fukushima incident.

This thing has been getting worse day by day and clearly has some way to go.

Right now it is looking like heading for Chernobyl scale, maybe not from the radiation perspective, although that is an ongoing thing, but as far as the site is concerned, it looks like it is going to be a no go zone for quite a while with horrendous clean up costs and logistics.

A significant problem with nuclear power is that nuclear accidents — like global warming caused by fossil fuels — have the potential to cause harm to the health of the unborn. Exposure to radiation can result in genetic mutation, and a damaged gene can be passed down for several generations. Can anyone really put a dollar value on a congenital defect?

— frank

It’s called the Dismal Science for a reason.

The media fearmongering of the nuclear accident in Japan is probably killing more people than the actual meltdown.

Then you have other plants being shut down including in Germany, which will mean more carbon emissions, by a pretty substantial amount.

Forget about the new reactors you list, the ones in Japan are already a very old design, much worse than new ones already existing.

MikeN, here’s a simple question for you. In the light of the nuclear plant malfunctions in Japan, if someone were to propose building a nuclear plant right next to your backyard, will you still be complaining about “media fearmongering”?

— frank

What is the world coming to, when MikeN’s position on nuclear power seems surprisingly similar to George Monbiot’s? (And mine, more or less.)

It’s actually rather hilarious, considering that it suggests that all of a sudden he accepts that high levels of carbon in the atmosphere can in fact be a threat to human life via climate disruption. It’s almost as if it’s a different person from the MikeN who harped for over a year about “hide the decline” and McIntyrian Auditing of minitutae undermining the whole of climate science – the very same science that leads us to the conclusion he’s talking about here.

That said, frank, I would dismiss bullshit like this as fearmongering. That’s in New York – half a world away from Japan. (It’s also not from the environmental anti-nuke movement, which is what I would expect MikeN is implying. It’s just plain old-fashioned fear.)

I”d be against the nuclear plant regardless of what’s happening in Japan. My point is that the irresponsible journalism in Japan may be causing a panic that produces more deaths than can result from this nuclear meltdown.

I think all the media focus on the nuclear plant is taking attention away from the worse problem – all the people who were killed by the earthquake and tsunami. -Kate

MikeN, then what will be your reasons for objecting to a nuclear plant right next to your backyard, if they’re different from the reasons stated by the media which you regard as “media fearmongering”?

— frank

Frank, the media fearmongering is in two types. There is the general fearmongering about nuclear power plants, and there is the fearmongering about the situation at the Japanese plant. I object to both, but my views are more in line with the first type, hence my objection to a nuclear plant, but here I am talking about the second version. Overstating the severity of an existing meltdown would not change my opinion of whether a plant should open nearby.

As a fellow climate change campaigner, I urge you to watch this movie.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/adamcurtis/2011/03/a_is_for_atom.html

Adam Curtis at his best

/seconded

wow – that comparison is thin …

if a hydroelectric disaster happens it’s over, but if a nuclear disaster happens, it just has started ….

after the tsunami japans coast could be populated again, but after a nuclear accident …

Tom,

My reaction to the coverage to date has been to wonder when someone in the press is going to get down to brass tacks. By this I mean that before we can talk about the impacts of radiation, or of this particular accident we need to have an accurate numerical quantification of what is happening. We may not have a full accounting of what has happened for many days or weeks to come.

Beyond the immediate question of exactly how bad this is, there are a whole host of questions which I for one do not fully understand. Japan had two nuclear weapons used on it during the second world war. Presently people live at both locations without any measurable ill effects that I know of. The difference between Chernbyl and the atomic bombings in terms of the long term effect on the local levels of background radiation is ultimately due to the far greater weight of radioactive material which was distributed by the Chernobyl incident.

If the IAEA (International Automic Energy Agency), an international treaty organization which reports to the UN General Assembly and Security Council, is to be trusted the most extreem effects of the Chernobyl incident were felt within the first three years. There is of course the Zone of Alienation which is an area surrounding the former power plant which has a persistant level of background radiation that is excessive, but for the surrounding regions and countries the health effects on the long term have been rather modest.

What is significant to me is the finding of the IAEA that the effect on the psychology of the people living in the region surrounding the Area of Alienation. An IAEA fact sheet makes the following statement:

The designation of the affected population as “victims” rather than “survivors” has led them to perceive themselves as helpless, weak and lacking control over their future. This, in turn, has led either to over cautious behavior and exaggerated health concerns, or to reckless conduct, such as consumption of mushrooms, berries and game from areas still designated as highly contaminated, overuse of alcohol and tobacco, and unprotected promiscuous sexual activity.

http://www.iaea.org/blog/Infolog/?page_id=25

Radiation and nuclear power is one of these issues were more knowledge is needfull, so that we might judge these questions rationally with due regard both for the risks of the particular technology, and for what the compairable risks of alternate technologies are.

http://www.iaea.org/newscenter/focus/chernobyl/

A link for those with an interest.

“My personal rule of thumb is that every death as a consequence of the japanese reactor problems will result in a million extra deaths as mitigation/transformation from fossil fuel decline is reduced.”

Comment by Gary P. at the Oil Drum.

From an historical perspective the fear of anything nuclear makes a kind of perverted sense. You have to remember that many of us (particularly baby boomers) grew up in an era that was dominated by the cold war and the constant threat of nuclear war and/or some radiation disaster. We are primed to react to any issue involving nuclear energy. The mass media of the day played up these fears through movies, tv shows, sci fi, etc. It really was a constant fear that was always at least in the background of all western societies.

As an aside one of my favourites is “Them”

… and at the same time the same mass media was telling everyone that nuclear power was both ‘safe’ and ‘cheap’ – although if you watch the video linked by dk.au’s post above, you’ll see that the public was being lied to.

Coming up to date, we find that while Japan loses control of its wayward nuclear power plants, its wind turbines –unfazed by either the earthquake or the tsunami — just keep on going… a lesson there, perhaps.

Kate: I’m about where you are on nuclear, in other words willing to swallow a nasty pill to help stave off fossil fuel sourced global warming. New nuclear technologies sound good, but I would think they need to go through a prototype stage before becoming commercialized. In the meantime, the greatest effort should be to develop renewables IMO.

A few comments:

What concerns me about nuclear is human error, which includes siting issues, and underestimating what can go wrong. Storage of used fuel rods in those water pools is a sign of underestimating what can go wrong.

I wonder how nuclear safety would fare in a world with far more nuclear power plants than we have now. Seems to me the odds of an accident would go up.

In order for nuclear to be safe, worst case scenario natural disasters have to be included in the planning. It may be comforting to think that events like the 9.0 magnitude quake in Japan are rare.

But, we’ve had four earthquakes of 9 magnitude or higher, in 51 years. Alaska 1964, the Indonesian quake and tsunami that killed a quarter million people, the great Chilean earthquake in 1960 at 9.5 magnitude, and now Japan. And earthquakes of 8-8.9 magnitude occur once a year on average.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richter_magnitude_scale

If this can happen in one of the world’s most technologically advanced and richest countries and one of the most politically stable countries, what will happen when less reliable regimes all over the world have embraced the Brave New World of a nuclear renaissance?

What happened in Japan is called Station Black Out – the loss of AC electrical power from the grid; power needed to run the cooling pumps. The tsunami knocked out diesel backup pumps, leaving the batteries as the only backup.

The Fukishima nuclear plant had 8 hours of battery backup for the cooling pumps.

We are now a week into the disaster in Japan.

In the U.S., there are 93 nuclear power plants with only 4 hours battery backup. The NRC only requires nuclear plants to have enough battery backup for a 4-8 hour situation.

Station blackout is one of the most likely causes of a nuclear accidents, according to the NRC

Sailrick: “I wonder how nuclear safety would fare in a world with far more nuclear power plants than we have now. Seems to me the odds of an accident would go up.”

Absolutely.

“Nuclear power is completely safe,” they try to assure us; and yet it’s clearly not. With every one more of these beasts built on our planet, the risk of something going wrong with one or more of them goes up.

That, together with the inability to dispose of the waste, and the creative accounting that has to be used to try to show cost-effectiveness — where none exists — is enough for me to realise that nuclear power is not an option.

In my opinion (which I’m well aware doesn’t count) the money would be better spent elsewhere.

I do not think that utilization of nuclear energy is categorically a bad thing. But we must look not only about budgets of energy and of money, but also of matter. It is not a good industry that produces a mixture of various chemical elements including radioisotopes of various lifetimes. It is a simple collorary of the 2nd law of thermodynamics that it requires low-entropy resources (energy or matter) to separate mixtures. Utilization of nuclear energy must go back to basic science, to find out a reaction which produces just a limited variety of manageable chemical elements and isotopes as by-products of electricity (catalyzed nuclear reactions).

If we succeed in all this, then its ultimate waste product, heat, will determine the limit of energy utilization, as envisaged by the Soviet climatologist Mikhail Budyko in his book “Climate Change” in 1974 (Japanese edition 1976, English edition 1977).

Common ground is certainly refreshing. Good job Kate!

George Monbiot makes it quite clear:

http://www.monbiot.com/2011/03/21/going-critical/

The options are fossil fuels, nuclear power and renewable. Most important is to phase out fossil fuels, right? So the question is what is the fastest way to do it? With renewable only or with renewable AND nuclear?

Renewable only. Nuclear power takes too long to implement, and sucks up funds better spent on developing renewables. Simples!

A question that I have is the following: wouldn’t underground nuclear reactors solve the problem of radiation leaking? let’s say, 100 meters below ground. If there is a problem, then the underground reactor is simply covered with dirt.

Sailrick nails it. If you look at most nuclear accidents, carelessness turns out to be a big factor. The disaster at Fukushima Daiichi was caused by a major earthquake near northern Japan and the quickly following tidal wave. However, in addition to the risk factors in the basic design of those old reactors, that coast-side plant had the backup generators in the basement where they were flooded out by the tidal wave.

I’ve studied the history of nuclear power in the U.S. It’s characterized by settling too early on the reactor types least costly to build and scaling them up to the point where fully effective containment was simply not affordable. Meanwhile, research into more advanced designs was shut down. Reference:

I think we need to restart that research, and carry it through. Of course, it may take another 20 or 30 years to get to the point where acceptably safe nuclear plant operation can be demonstrated. Until then, we need to get solar, wind, and other forms of renewable power into operation as widely as possible.

Sailrick writes: “I wonder how nuclear safety would fare in a world with far more nuclear power plants than we have now. Seems to me the odds of an accident would go up.”

I think the odds would go down, because of the greater experience at building and operating the plants. It still could be that accidents would be more numerous than today, just because the plants were more numerous. This is not a question easily answered.

Achilleas Margaritis asks about placing reactors underground. The problem there is getting rid of the waste heat. It’s why reactors are usually near a source of plentiful water — a river, lake, or ocean.

There are technical solutions to this problem: ways to use closed-cycle cooling systems. Of course they are more expensive than current designs, and need much more development.

? At some time doesn’t nuclear energy become a huge source of heat?

Nuclear energy is outside the well-calculated realm of solar warming, infrared, and carbon combustion.

If US nuke energy was 807 billion kWh in 2010 – and that is 30% of the world.. then the world generated about 1.4 trillion kWh of nuclear power.

Doesn’t that get added to the watts per square meter?

Does that mean that a nuke power contributes about a third of a watt per square meter per year?

“Does that mean that a nuke power contributes about a third of a watt per square meter per year?”

I may have miscalculated this but I get a value of 0,002 watt per square meter for nuclear power generation. This walue does not include the seweral hundered small reactors onboard submarines and other vessels.

Fossil fuels are producing heat in the same way than nuclear power. However, there is a difference between these heat sources and the greenhouse effect. The contribution of energy production to global warming in the form of direct heating is minuscule. Greenhouse gases are preventing the heat to escaping to the space. So without man made greenhouse gases the heat from energy generation would not heat up the atmosphere in the same way as the greenhouse gases do.

Thank you so much for the recalculation. Nice to have it quantifed.