Kaitlin Naughten, British Antarctic Survey; Jan De Rydt, Northumbria University, Newcastle, and Paul Holland, British Antarctic Survey

Originally published at The Conversation based on research published in Nature Climate Change

The rate at which the warming Southern Ocean melts the West Antarctic ice sheet will speed up rapidly over the course of this century, regardless of how much emissions fall in coming decades, our new research suggests. This ocean-driven melting is expected to increase sea-level rise, with consequences for coastal communities around the world.

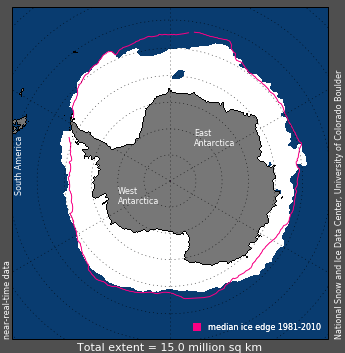

The Antarctic ice sheet, the world’s largest volume of land-based ice, is a system of interconnected glaciers comprised of snowfall that remains year-round. Coastal ice shelves are the floating edges of this ice sheet which stabilise the glaciers behind them. The ocean melts these ice shelves from below, and if melting increases and an ice shelf thins, the speed at which these glaciers discharge fresh water into the ocean increases too and sea levels rise.

In West Antarctica, particularly the Amundsen Sea, this process has been underway for decades. Ice shelves are thinning, glaciers are flowing faster towards the ocean and the ice sheet is shrinking. While ocean temperature measurements in this region are limited, modelling suggests it may have warmed as a result of climate change.

We chose to model the Amundsen Sea because it is the most vulnerable sector of the ice sheet. We used a regional ocean model to find out how ice-shelf melting will change here between now and 2100. How much melting can be prevented by reducing carbon emissions and slowing the rate of climate change – and how much is now unavoidable, no matter what we do?

Rapid change is locked in

We used the UK’s national supercomputer ARCHER2 to run many different simulations of the 21st century, totalling over 4,000 years of ocean warming and ice-shelf melting in the Amundsen Sea.

We considered different trajectories for fossil fuel burning, from the best-case scenario where global warming is limited to 1.5°C in line with the Paris Agreement, to the worst, in which coal, oil and gas use is uncontrolled. We also considered the influence of natural variations in the climate, such as the timing of events such as El Niño.

The results are worrying. In all simulations there is a rapid increase over the course of this century in the rate of ocean warming and ice-shelf melting. Even the best-case scenario in which warming halts at 1.5°C, something that is considered ambitious by many experts, entails a threefold increase in the historical rate of warming and melting.

What’s more, there is little to no difference between the scenarios up to 2045. Ocean warming and ice-shelf melting in the 1.5°C scenario is statistically the same as in a mid-range scenario, which is closer to what existing pledges to reduce fossil fuel use over the coming decades would produce.

The worst-case scenario shows more melting than the others, but only from around mid-century onwards, and many experts think this amount of future fossil fuel burning is unrealistic anyway.

The results imply that we are now committed to rapid ocean warming in the Amundsen Sea until at least 2100, regardless of international policies on fossil fuels.

The increases in warming and melting are the result of ocean currents strengthening and driving more warm water from the deep ocean towards the shallower ice shelves along the coast. Other studies have suggested this process is behind the ice shelf thinning measured by satellites.

How much will the sea level rise?

Melting ice shelves are a major cause of sea-level rise, but not the whole story. We can’t put a number on how much sea levels will rise without also simulating the flow of Antarctic glaciers and the rate of snow accumulating on the ice sheet, which our model didn’t include.

But we have every reason to believe that increased ice-shelf melting in this region will cause the rate at which sea levels are rising to speed up.

The West Antarctic ice sheet is already contributing substantially to global sea-level rise and is losing about 80 billion tonnes of ice a year. It contains enough ice to cause up to 5 metres of sea-level rise, but we don’t know how much of it will melt, and how quickly. Our colleagues around the world are working hard to answer this question.

Courage and hope

There are some consequences of climate change that can no longer be avoided, no matter how much fossil fuel use falls. Substantial melting of West Antarctica up to 2100 may now be one of them.

How do you tell a bad news story? The conventional wisdom is that you’re supposed to give people hope: to say that there’s a disaster behind one door, but we can avoid it if only we choose a different one. What do you do when your science tells you that all doors lead to the same disaster?

Kate Marvel, an atmospheric scientist, said that when it comes to climate change, “we need courage, not hope … Courage is the resolve to do well without the assurance of a happy ending”. In this case, courage means shifting our attention to the longer term.

The future will not end in 2100, even if most people reading this will no longer be around. Our simulations of the 1.5°C scenario show ice-shelf melting starting to plateau by the end of the century, suggesting that further changes in the 22nd century and beyond may still be preventable. Reducing sea-level rise after 2100, or even slowing it down, could save many coastal cities.

Courage means accepting the need to adapt, protecting coastal communities where it’s possible to do so, and rebuilding or abandoning them where it’s not. By predicting future sea-level rise in advance, we’ll have time to plan for it – rather than wait until the ocean is on our doorstep.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Kaitlin Naughten, Ocean-Ice Modeller, British Antarctic Survey; Jan De Rydt, Associate Professor of Polar Glaciology and Oceanography, Northumbria University, Newcastle, and Paul Holland, Ocean and Ice Scientist, British Antarctic Survey

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.