A year ago today, an unidentified hacker published a zipped folder in several locations online. In this folder were approximately one thousand emails and three thousand files which had been stolen from the backup server of the Climatic Research Unit in the UK, a top centre for global temperature analysis and climate change studies. As links to the folder were passed around on blogs and online communities, a small group of people sorted through the emails, picking out a handful of phrases that could be seen as controversial, and developing a narrative which they pushed to the media with all their combined strength. “A lot is happening behind the scenes,” one blog administrator wrote. “It is not being ignored. Much is being coordinated among major players and the media. Thank you very much. You will notice the beginnings of activity on other sites now. Here soon to follow.”

This was not the work of a computer-savvy teenager that liked to hack security systems for fun. Whoever the thief was, they knew what they were looking for. They knew how valuable the emails could be in the hands of the climate change denial movement.

Skepticism is a worthy quality in science, but denial is not. A skeptic will only accept a claim given sufficient evidence, but a denier will cling to their beliefs regardless of evidence. They will relentlessly attack arguments that contradict their cause, using talking points that are full of misconceptions and well-known to be false, while blindly accepting any argument that seems to support their point of view. A skeptic is willing to change their mind. A denier is not.

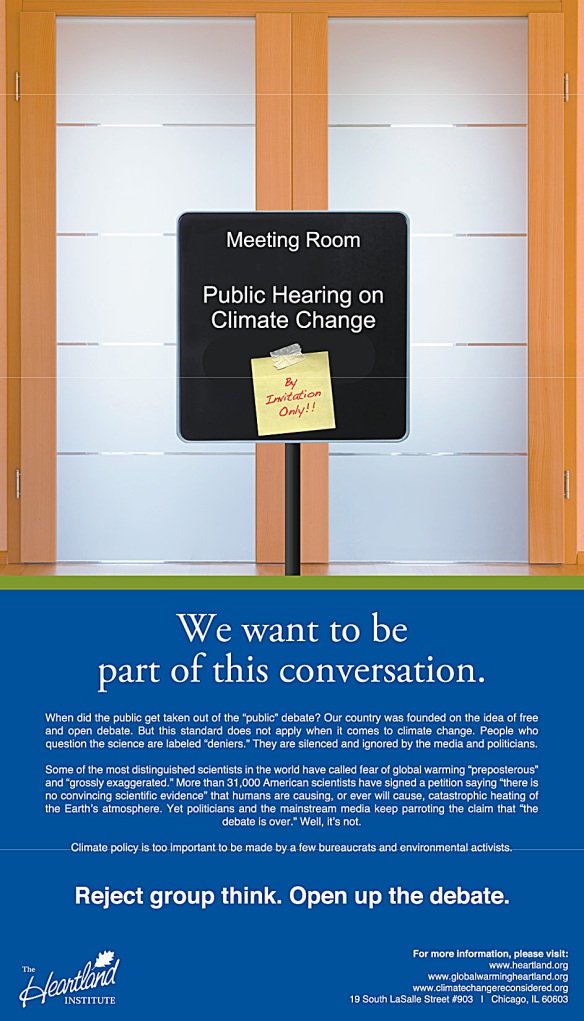

There are many examples of denial in our society, but perhaps the most powerful and pervasive is climate change denial. We’ve been hearing the movement’s arguments for years, ranging from illogic (“climate changed naturally in the past, so it must be natural now“) to misrepresentation (“global warming stopped in 1998“) to flat-out lies (“volcanoes emit more carbon dioxide than humans“). Of course, climate scientists thought of these objections and ruled them out long before you and I even knew what global warming was, so in recent years, the arguments of deniers were beginning to reach a dead end. The Copenhagen climate summit was approaching, and the public was beginning to understand the basic science of human-caused climate change, even realize that the vast majority of the scientific community was concerned about it. A new strategy for denial and delay was needed – ideally, for the public to lose trust in researchers. Hence, the hack at CRU, and the beginning of a disturbing new campaign to smear the reputations of climate scientists.

The contents of the emails were spun in a brilliant exercise of selective quotation. Out of context, phrases can be twisted to mean any number of things – especially if they were written as private correspondence with colleagues, rather than with public communication in mind. Think about all the emails you have sent in the past decade. Chances are, if someone tried hard enough, they could make a few sentences you had written sound like evidence of malpractice, regardless of your real actions or intentions.

Consequently, a mathematical “trick” (clever calculation) to efficiently analyse data was reframed as a conspiracy to “trick” (deceive) the public into believing the world was warming. Researchers discussed how to statistically isolate and “hide the decline” in problematic tree ring data that was no longer measuring what it used to, but this quote was immediately twisted to claim that the decline was in global temperatures: the world is cooling and scientists are hiding it from us!

Other accusations were based not on selective misquotation but on a misunderstanding of the way science works. When the researchers discussed what they felt were substandard papers that should not be published, many champions of the stolen emails shouted accusations that scientists were censoring their critics, as if all studies, no matter how weak their arguments, had a fundamental right to be published. Another email, in which a researcher privately expressed a desire to punch a notorious climate change denier, was twisted into an accusation that the scientists threatened people who disagreed with them. How was it a threat if the action was never intended to materialize, and if the supposed target was never aware of it?

These serious and potentially damaging allegations, which, upon closer examination, are nothing more than grasping at straws, were not carefully examined and evaluated by journalists – they were repeated. Early media reports bordered on the hysterical. With headlines such as “The final nail in the coffin of anthropogenic global warming” and “The worst scientific scandal of our generation“, libelous claims and wild extrapolations were published mere days after the emails were distributed. How could journalists have possibly had time to carefully examine the contents of one thousand emails? It seems much more likely that they took the short-cut of repeating the narrative of the deniers without assessing its accuracy.

Even if, for the sake of argument, all science conducted by the CRU was fraudulent, our understanding of global warming would not change. The CRU runs a global temperature dataset, but so do at least six other universities and government agencies around the world, and their independent conclusions are virtually identical. The evidence for human-caused climate change is not a house of cards that will collapse as soon as one piece is taken away. It’s more like a mountain: scrape a couple of pebbles off the top, but the mountain is still there. For respected newspapers and media outlets to ignore the many independent lines of evidence for this phenomenon in favour of a more interesting and controversial story was blatantly irresponsible, and almost no retractions or apologies have been published since.

The worldwide media attention to this so-called scandal had a profound personal impact on the scientists involved. Many of them received death threats and hate mail for weeks on end. Dr. Phil Jones, the director of CRU, was nearly driven to suicide. Another scientist, who wishes to remain anonymous, had a dead animal dumped on his doorstep and now travels with bodyguards. Perhaps the most wide-reaching impact of the issue was the realization that private correspondence was no longer a safe environment. This fear only intensified when the top climate modelling centre in Canada was broken into, in an obvious attempt to find more material that could be used to smear the reputations of climate scientists. For an occupation that relies heavily on email for cross-national collaboration on datasets and studies, the pressure to write in a way that cannot be taken out of context – a near-impossible task – amounts to a stifling of science.

Before long, the investigations into the contents of the stolen emails were completed, and one by one, they came back clear. Six independent investigations reached basically the same conclusion: despite some reasonable concerns about data archival and sharing at CRU, the scientists had shown integrity and honesty. No science had been falsified, manipulated, exaggerated, or fudged. Despite all the media hullabaloo, “climategate” hadn’t actually changed anything.

Sadly, by the time the investigations were complete, the media hullabaloo had died down to a trickle. Climategate was old news, and although most newspapers published stories on the exonerations, they were generally brief, buried deep in the paper, and filled with quotes from PR spokespeople that insisted the investigations were “whitewashed”. In fact, Scott Mandia, a meteorology professor, found that media outlets devoted five to eleven times more stories to the accusations against the scientists than they devoted to the resulting exonerations of the scientists.

Six investigations weren’t enough, though, for some stubborn American politicians who couldn’t let go of the article of faith that Climategate was proof of a vast academic conspiracy. Senator James Inhofe planned a McCarthy-like criminal prosecution of seventeen researchers, most of whom had done nothing more than occasionally correspond with the CRU scientists. The Attorney General of Virginia, Ken Cuccinelli, repeatedly filed requests to investigate Dr. Michael Mann, a prominent paleoclimatic researcher, for fraud, simply because a twelve-year-old paper by Mann had some statistical weaknesses. Ironically, the Republican Party, which prides itself on fiscal responsibility and lower government spending, continues to advocate wasting massive sums of money conducting inquiries which have already been completed multiple times.

Where are the politicians condemning the limited resources spent on the as yet inconclusive investigations into who stole these emails, and why? Who outside the scientific community is demanding apologies from the hundreds of media outlets that spread libelous accusations without evidence? Why has the ongoing smear campaign against researchers studying what is arguably the most pressing issue of our time gone largely unnoticed, and been aided by complacent media coverage?

Fraud is a criminal charge, and should be treated as such. Climate scientists, just like anyone else, have the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. They shouldn’t have to endure this endless harassment of being publicly labelled as frauds without evidence. However, the injustice doesn’t end there. This hate campaign is a dangerous distraction from the consequences of global climate change, a problem that becomes more difficult to solve with every year we delay. The potential consequences are much more severe, and the time we have left to successfully address it is much shorter, than the vast majority of the public realizes. Unfortunately, powerful forces are at work to keep it that way. This little tussle about the integrity of a few researchers could have consequences millennia from now – if we let it.

Update: Many other climate bloggers are doing Climategate anniversary pieces. Two great ones I read today were Bart Verheggen’s article and the transcript of John Cook’s radio broadcast. Be sure to check them out!

S. Fred Singer is an atmospheric physicist and retired environmental science professor. He has rarely published in scientific journals since the 1960s, but he is very visible in the media. In recent years, he has claimed that the Earth has been cooling since 1998 (in 2006), that the Earth is warming, but it is natural and unstoppable (in 2007), and that the warming is artificial and due to the urban heat island effect (in 2009).

S. Fred Singer is an atmospheric physicist and retired environmental science professor. He has rarely published in scientific journals since the 1960s, but he is very visible in the media. In recent years, he has claimed that the Earth has been cooling since 1998 (in 2006), that the Earth is warming, but it is natural and unstoppable (in 2007), and that the warming is artificial and due to the urban heat island effect (in 2009). Richard Lindzen, also an atmospheric physicist, is far more active in the scientific community than Singer. However, most of his publications, including the prestigious IPCC report to which he contributed, conclude that climate change is real and caused by humans. He has published two papers stating that climate change is not serious: a 2001 paper hypothesizing that clouds would provide a negative feedback to cancel out global warming, and a 2009 paper claiming that climate sensitivity (the amount of warming caused by a doubling of carbon dioxide) was very low. Both of these ideas were rebutted by the academic community, and Lindzen’s methodology criticized. Lindzen has even publicly retracted his 2001 cloud claim. Therefore, in his academic life, Lindzen appears to be a mainstream climate scientist – contributing to assessment reports, abandoning theories that are disproved, and publishing work that affirms the theory of anthropogenic climate change. However, when Lindzen talks to the media, his statements change. He has implied that the world is not warming by calling attention to the lack of warming in the Antarctic (in 2004) and the thickening of some parts of the Greenland ice sheet (in 2006), without explaining that both of these apparent contradictions are well understood by scientists and in no way disprove warming. He has also claimed that the observed warming is minimal and natural (in 2006).

Richard Lindzen, also an atmospheric physicist, is far more active in the scientific community than Singer. However, most of his publications, including the prestigious IPCC report to which he contributed, conclude that climate change is real and caused by humans. He has published two papers stating that climate change is not serious: a 2001 paper hypothesizing that clouds would provide a negative feedback to cancel out global warming, and a 2009 paper claiming that climate sensitivity (the amount of warming caused by a doubling of carbon dioxide) was very low. Both of these ideas were rebutted by the academic community, and Lindzen’s methodology criticized. Lindzen has even publicly retracted his 2001 cloud claim. Therefore, in his academic life, Lindzen appears to be a mainstream climate scientist – contributing to assessment reports, abandoning theories that are disproved, and publishing work that affirms the theory of anthropogenic climate change. However, when Lindzen talks to the media, his statements change. He has implied that the world is not warming by calling attention to the lack of warming in the Antarctic (in 2004) and the thickening of some parts of the Greenland ice sheet (in 2006), without explaining that both of these apparent contradictions are well understood by scientists and in no way disprove warming. He has also claimed that the observed warming is minimal and natural (in 2006). Finally, Patrick Michaels is an ecological climatologist who occasionally publishes peer-reviewed studies, but none that support his more outlandish claims. In 2009 alone, Michaels said that the observed warming is below what computer models predicted, that natural variations in oceanic cycles such as El Niño explain most of the warming, and that human activity explains most of the warming but it’s nothing to worry about because technology will save us (cached copy, as the original was taken down).

Finally, Patrick Michaels is an ecological climatologist who occasionally publishes peer-reviewed studies, but none that support his more outlandish claims. In 2009 alone, Michaels said that the observed warming is below what computer models predicted, that natural variations in oceanic cycles such as El Niño explain most of the warming, and that human activity explains most of the warming but it’s nothing to worry about because technology will save us (cached copy, as the original was taken down).