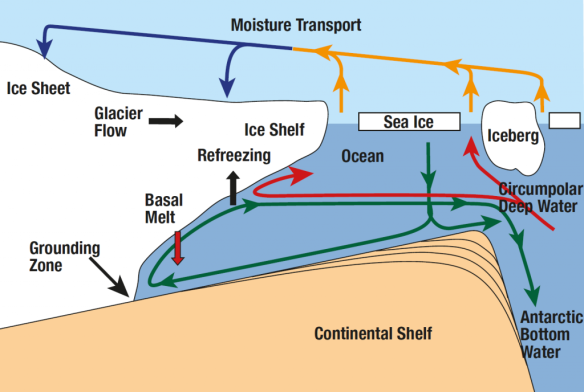

An ice sheet forms when snow falls on land, compacts into ice, and forms a system of interconnected glaciers which gradually flow downhill like play-dough. In Antarctica, it is so cold that the ice flows right into the ocean before it melts, sometimes hundreds of kilometres from the coast. These giant slabs of ice, floating on the ocean while still attached to the continent, are called ice shelves.

For an ice sheet to have constant size, the mass of ice added from snowfall must equal the mass lost due to melting and calving (when icebergs break off). Since this ice loss mainly occurs at the edges, the rate of ice loss will depend on how fast glaciers can flow towards the edges.

Ice shelves slow down this flow. They hold back the glaciers behind them in what is known as the “buttressing effect”. If the ice shelves were smaller, the glaciers would flow much faster towards the ocean, melting and calving more ice than snowfall inland could replace. This situation is called a “negative mass balance”, which leads directly to global sea level rise.

Ice shelves are perhaps the most important part of the Antarctic ice sheet for its overall stability. Unfortunately, they are also the part of the ice sheet most at risk. This is because they are the only bits touching the ocean. And the Antarctic ice sheet is not directly threatened by a warming atmosphere – it is threatened by a warming ocean.

The atmosphere would have to warm outrageously in order to melt the Antarctic ice sheet from the top down. Snowfall tends to be heaviest when temperatures are just below 0°C, but temperatures at the South Pole rarely go above -20°C, even in the summer. So atmospheric warming will likely lead to a slight increase in snowfall over Antarctica, adding to the mass of the ice sheet. Unfortunately, the ocean is warming at the same time. And a slightly warmer ocean will be very good at melting Antarctica from the bottom up.

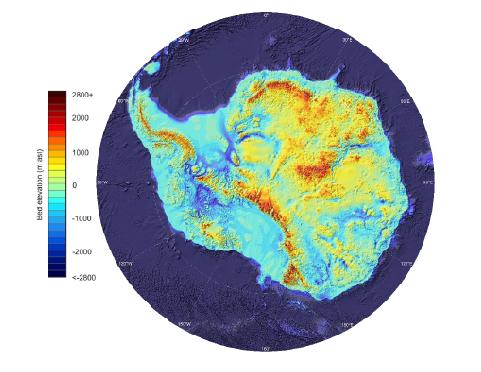

This is partly because ice melts faster in water than it does in air, even if the air and the water are the same temperature. But the ocean-induced melting will be exacerbated by some unlucky topography: over 40% of the Antarctic ice sheet (by area) rests on bedrock that is below sea level.

Elevation of the bedrock underlying Antarctica. All of the blue regions are below sea level. (Figure 9 of Fretwell et al.)

This means that ocean water can melt its way in and get right under the ice, and gravity won’t stop it. The grounding lines, where the ice sheet detaches from the bedrock and floats on the ocean as an ice shelf, will retreat. Essentially, a warming ocean will turn more of the Antarctic ice sheet into ice shelves, which the ocean will then melt from the bottom up.

This situation is especially risky on a retrograde bed, where bedrock gets deeper below sea level as you go inland – like a giant, gently sloping bowl. Retrograde beds occur because of isostatic loading (the weight of an ice sheet pushes the crust down, making the tectonic plate sit lower in the mantle) as well as glacial erosion (the ice sheet scrapes away the surface bedrock over time). Ice sheets resting on retrograde beds are inherently unstable, because once the grounding lines reach the edge of the “bowl”, they will eventually retreat all the way to the bottom of the “bowl” even if the ocean water intruding beneath the ice doesn’t get any warmer. This instability occurs because the melting point temperature of water decreases as you go deeper in the ocean, where pressures are higher. In other words, the deeper the ice is in the ocean, the easier it is to melt it. Equivalently, the deeper a grounding line is in the ocean, the easier it is to make it retreat. In a retrograde bed, retreating grounding lines get deeper, so they retreat more easily, which makes them even deeper, and they retreat even more easily, and this goes on and on even if the ocean stops warming.

Which brings us to Terrifying Paper #1, by Rignot et al. A decent chunk of West Antarctica, called the Amundsen Sea Sector, is melting particularly quickly. The grounding lines of ice shelves in this region have been rapidly retreating (several kilometres per year), as this paper shows using satellite data. Unfortunately, the Amundsen Sea Sector sits on a retrograde bed, and the grounding lines have now gone past the edge of it. This retrograde bed is so huge that the amount of ice sheet it underpins would cause 1.2 metres of global sea level rise. We’re now committed to losing that ice eventually, even if the ocean stopped warming tomorrow. “Upstream of the 2011 grounding line positions,” Rignot et al., write, “we find no major bed obstacle that would prevent the glaciers from further retreat and draw down the entire basin.”

They look at each source glacier in turn, and it’s pretty bleak:

- Pine Island Glacier: “A region where the bed elevation is smoothly decreasing inland, with no major hill to prevent further retreat.”

- Smith/Kohler Glaciers: “Favorable to more vigorous ice shelf melt even if the ocean temperature does not change with time.”

- Thwaites Glacier: “Everywhere along the grounding line, the retreat proceeds along clear pathways of retrograde bed.”

Only one small glacier, Haynes Glacier, is not necessarily doomed, since there are mountains in the way that cut off the retrograde bed.

From satellite data, you can already see the ice sheet speeding up its flow towards the coast, due to the loss of buttressing as the ice shelves thin: “Ice flow changes are detected hundreds of kilometers inland, to the flanks of the topographic divides, demonstrating that coastal perturbations are felt far inland and propagate rapidly.”

It will probably take a few centuries for the Amundsen Sector to fully disintegrate. But that 1.2 metres of global sea level rise is coming eventually, on top of what we’ve already seen from other glaciers and thermal expansion, and there’s nothing we can do to stop it (short of geoengineering). We’re going to lose a lot of coastal cities because of this glacier system alone.

Terrifying Paper #2, by Mengel & Levermann, examines the Wilkes Basin Sector of East Antarctica. This region contains enough ice to raise global sea level by 3 to 4 metres. Unlike the Amundsen Sector, we aren’t yet committed to losing this ice, but it wouldn’t be too hard to reach that point. The Wilkes Basin glaciers rest on a system of deep troughs in the bedrock. The troughs are currently full of ice, but if seawater got in there, it would melt all the way along the troughs without needing any further ocean warming – like a very bad retrograde bed situation. The entire Wilkes Basin would change from ice sheet to ice shelf, bringing along that 3-4 metres of global sea level rise.

It turns out that the only thing stopping seawater getting in the troughs is a very small bit of ice, equivalent to only 8 centimetres of global sea level rise, which Mengel & Levermann nickname the “ice plug”. As long as the ice plug is there, this sector of the ice sheet is stable; but take the ice plug away, and the whole thing will eventually fall apart even if the ocean stops warming. Simulations from an ice sheet model suggest it would take at least 200 years of increased ocean temperature to melt this ice plug, depending on how much warmer the ocean got. 200 years sounds like a long time for us to find a solution to climate change, but it actually takes much longer than that for the ocean to cool back down after it’s been warmed up.

This might sound like all bad news. And you’re right, it is. But it can always get worse. That means we can always stop it from getting worse. That’s not necessarily good news, but at least it’s empowering. The sea level rise we’re already committed to, whether it’s 1 or 2 or 5 metres, will be awful. But it’s much better than 58 metres, which is what we would get if the entire Antarctic ice sheet melted. Climate change is not an all-or-nothing situation; it falls on a spectrum. We will have to deal with some amount of climate change no matter what. The question of “how much” is for us to decide.