Around 55 million years ago, an abrupt global warming event triggered a highly corrosive deep-water current to flow through the North Atlantic Ocean. This process, suggested by new climate model simulations, resolves a long-standing mystery regarding ocean acidification in the deep past.

The rise of CO2 that led to this dramatic acidification occurred during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), a period when global temperatures rose by around 5°C over several thousand years and one of the largest-ever mass extinctions in the deep ocean occurred.

The PETM, 55 million years ago, is the most recent analogue to present-day climate change that researchers can find. Similarly to the warming we are experiencing today, the PETM warming was a result of increases in atmospheric CO2. The source of this CO2 is unclear, but the most likely explanations include methane released from the seafloor and/or burning peat.

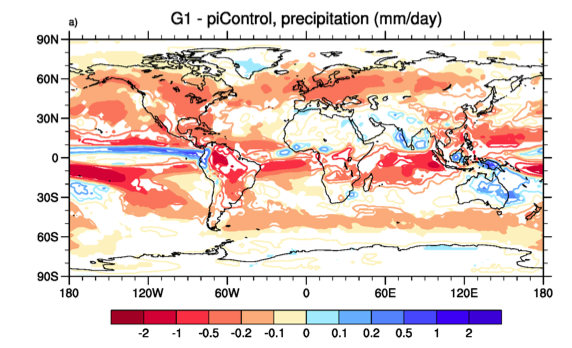

During the PETM, like today, emissions of CO2 were partially absorbed by the ocean. By studying sediment records of the resulting ocean acidification, researchers can estimate the amount of CO2 responsible for warming. However, one of the great mysteries of the PETM has been why ocean acidification was not evenly spread throughout the world’s oceans but was so much worse in the Atlantic than anywhere else.

This pattern has also made it difficult for researchers to assess exactly how much CO2 was added to the atmosphere, causing the 5°C rise in temperatures. This is important for climate researchers as the size of the PETM carbon release goes to the heart of the question of how sensitive global temperatures are to greenhouse gas emissions.

Solving the mystery of these remarkably different patterns of sediment dissolution in different oceans is a vital key to understanding the rapid warming of this period and what it means for our current climate.

A study recently published in Nature Geoscience shows that my co-authors Katrin Meissner, Tim Bralower and I may have cracked this long-standing mystery and revealed the mechanism that led to this uneven ocean acidification.

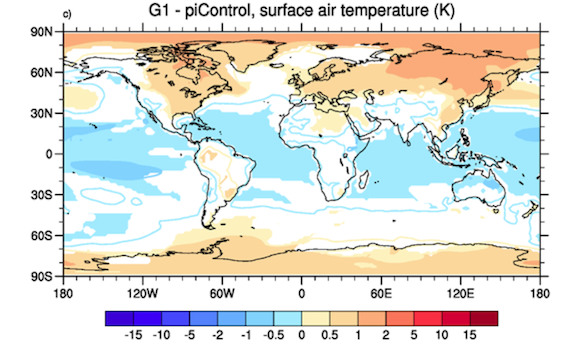

We now suspect that atmospheric CO2 was not the only contributing factor to the remarkably corrosive Atlantic Ocean during the PETM. Using global climate model simulations that replicated the ocean basins and landmasses of this period, it appears that changes in ocean circulation due to warming played a key role.

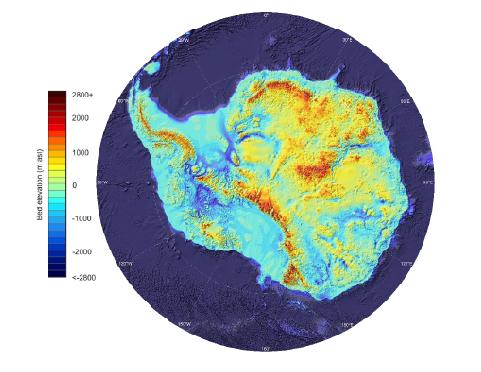

55 million years ago, the ocean floor looked quite different than it does today. In particular, there was a ridge on the seafloor between the North and South Atlantic, near the equator. This ridge completely isolated the deep North Atlantic from other oceans, like a giant bathtub on the ocean floor.

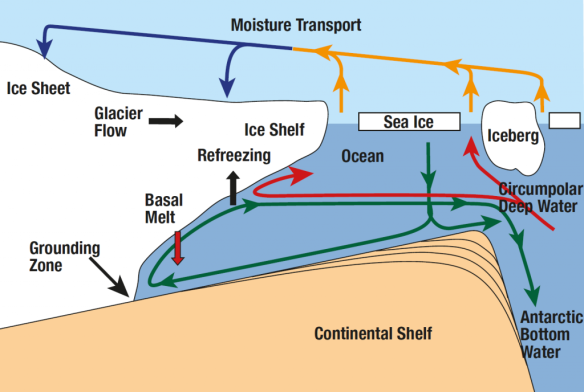

In our simulations this “bathtub” was filled with corrosive water, which could easily dissolve calcium carbonate. This corrosive water originated in the Arctic Ocean and sank to the bottom of the Atlantic after mixing with dense salty water from the Tethys Ocean (the precursor to today’s Mediterranean, Black, and Caspian Seas).

Our simulations then reproduced the effects of the PETM as the surface of the Earth warmed in response to increases in CO2. The deep ocean, including the corrosive bottom water, gradually warmed in response. As it warmed it became less dense. Eventually the surface water became denser than the warming deep water and started to sink, causing the corrosive deep water mass to spill over the ridge – overflowing the “giant bath tub”.

The corrosive water then spread southward through the Atlantic, eastward through the Southern Ocean, and into the Pacific, dissolving sediments as it went. It became more diluted as it travelled and so the most severe effects were felt in the South Atlantic. This pattern agrees with sediment records, which show close to 100% dissolution of calcium carbonate in the South Atlantic.

If the acidification event occurred in this manner it has important implications for how strongly the Earth might warm in response to increases in atmospheric CO2.

If the high amount of acidification seen in the Atlantic Ocean had been caused by atmospheric CO2 alone, that would suggest a huge amount of CO2 had to go into the atmosphere to cause 5°C warming. If this were the case, it would mean our climate was not very sensitive to CO2.

But our findings suggest other factors made the Atlantic far more corrosive than the rest of the world’s oceans. This means that sediments in the Atlantic Ocean are not representative of worldwide CO2 concentrations during the PETM.

Comparing computer simulations with reconstructed ocean warming and sediment dissolution during the event, we could narrow our estimate of CO2 release during the event to 7,000 – 10,000 GtC. This is probably similar to the CO2 increase that will occur in the next few centuries if we burn most of the fossil fuels in the ground.

To give this some context, today we are emitting CO2 into the atmosphere at least 10 times faster than than the natural CO2 emissions that caused the PETM. Should we continue to burn fossil fuels at the current rate, we are likely to see the same temperature increase in the space of a few hundred years that took a few thousand years 55 million years ago.

This is an order of magnitude faster and it is likely the impacts from such a dramatic change will be considerably stronger.

Written with the help of my co-authors Katrin and Tim, as well as our lab’s communications manager Alvin Stone.