Cross-posted from NextGen Journal

“That’s some global warming”, Fox News proudly announced. “Rare winter storm dumps several inches of snow across South.” It’s cold outside, and/or it’s snowing, so therefore global warming can’t be happening. Impeccable logic, or rampant misconception?

It happened last winter, and again so far this season: unusual snow and extreme cold thrashed the United States, Europe, and Russia. Climate change deniers, with a response as predictable as Newton’s Laws, trumpeted the conditions as undeniable proof that the world simply could not be warming. Even average people, understandably confused by conflicting media reports, started to wonder if global warming was really such a watertight theory.

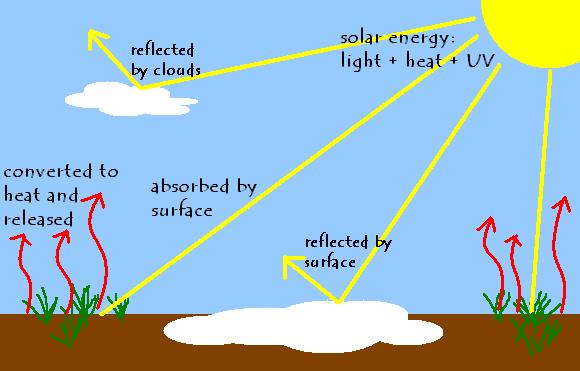

But sit and think about it for a minute. If it’s cold right now in the place where you live, that doesn’t mean it’s cold everywhere else. It’s simply not possible to look at your little corner of the world and extrapolate those conditions to the entire planet. There’s a reason it’s called global warming, and not “everywhere-all-the-time warming”. Climate change increases the amount of thermal energy on our planet, but that doesn’t mean the extra energy will be distributed equally.

That said, an interesting weather condition has been prominent over the past month, telling a fascinating story that begins in the Arctic. At the recent American Geophysical Union conference in San Fransisco, the largest annual gathering of geoscientists in the world, NOAA scientist Jim Overland described the situation.

Usually in winter, the air masses above the Arctic have low pressure, and the entire area is surrounded by a circular vortex of wind currents, keeping the frigid polar air contained. Everything is what you’d expect: a cold Arctic and mild continents. These conditions are known as the positive phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO), an index of fluctuating wind and temperature patterns that impacts weather on both sides of the Atlantic.

The negative phase is different, and quite rare: high pressure over the Arctic forces the cold air to spill out over North America and Eurasia, allowing warm air to rush in to the polar region. Meteorologist Jeff Masters has a great analogy for a negative NAO: it’s “kind of like leaving the refrigerator door ajar–the refrigerator warms up, but all of the cold air spills out into the house.” The Arctic becomes unusually warm, and the temperate regions of the surrounding continents become unusually cold. Nobody visually depicts this pattern better than freelance journalist Peter Sinclair:

So what’s been causing this rare shift to the negative NAO the past two winters? In fact, global warming itself could easily be the culprit. Strong warming over the Arctic is melting the sea ice, not just in the summer, but year-round. Open water in the Arctic Ocean during the winter allows heat to flow from the ocean to the atmosphere, creating the high pressure needed for a negative NAO to materialize. Paradoxically, the cold, snowy weather many of us are experiencing could be the result of a warming planet.

An emerging debate among scientists questions which force will win out over winters in Europe and North America: the cooling influence of more negative NAO conditions, or the warming influence of climate change itself? A recent study in the Journal of Geophysical Research predicts a threefold increase in the likelihood of cold winters over “large areas including Europe” as global warming develops. On the other hand, scientists at GISS, the climate change team at NASA, counter that extreme lows in sea ice over the past decade have not always led to cold winters in Europe, as 7 out the past 10 winters there have been warmer than average.

Amid this new frontier in climate science, one thing is virtually certain: global warming has not stopped, despite what Fox News tells you. In fact, despite localized record cold, 2010 is expected to be either the warmest year on record or tied for first with 2005 (final analysis is not yet complete). What you see in your backyard isn’t always a representative sample.