I recently wrote this term paper for my world issues course. Enjoy.

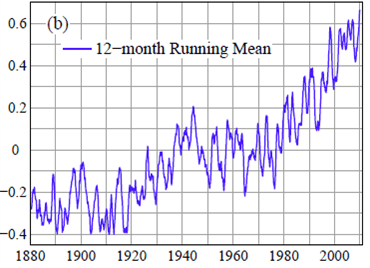

There are many questions which remain controversial among scientists, but the existence of human-caused climate change is not one of them. Over 97% of publishing climatologists (Doran and Zimmerman, 2009), virtually 100% of peer-reviewed studies (Oreskes, 2004), and every scientific organization in the world (Logical Science, 2006) agree that humans are causing the Earth to warm. As Donald Kennedy, former editor-in-chief of the prestigious journal Science, says, “Consensus as strong as the one that has developed around this topic is rare in science.”

However, this consensus does not extend to the general public. On a particularly cold day, the cashier at the grocery store will say to you, “So much for global warming.” Over Thanksgiving dinner, your uncle will openly wonder if the warming in the Arctic is just part of a natural cycle. Your local newspaper will print letters to the editor almost daily claiming that, as CO2 is natural and essential to life, we shouldn’t worry about climate change.

What is the reason for this disconnection between scientific opinion and public opinion? There are obviously many factors involved, but it is probable that this discrepancy exists partly because of the widespread media coverage of scientists who do not accept anthropogenic climate change. Anyone with an Internet connection or a newspaper subscription will be able to tell you that many scientists think global warming is natural or nonexistent. As we know, these scientists are in the vast minority, and they have been unable to support their views in the peer-reviewed literature. The key question, therefore, is this: Why are so many of them still publicizing their beliefs so prominently?

Two plausible outcomes exist. Firstly, a scientist who could not prove a hypothesis could still feel that it was an idea worth consideration, and would want to capture the imagination of other scientists so it would be studied more closely. Alternatively, a scientist might be willing to keep the public confused about climate change. For example, scientists employed by the fossil fuel industry, or by organizations with strong laissez-faire agendas, could be motivated to spread rumours about weaknesses in the anthropogenic climate change theory. So, do these skeptics honestly doubt the integrity of climate science? Or are they being paid to manufacture doubt?

To distinguish between these two motives, it is important to understand a distinct difference in the formation of scientific opinions and political opinions. In science, one should examine all the evidence and then develop a logical conclusion. However, it is all too common in politics, lobbying, and the media for one to choose a convenient conclusion, then build evidence around it. This process is akin to an “ends justify the means” approach. The means (evidence and methods) are justified as long as they support the ends (a preconceived conclusion). In contrast, science, which is continually striving for a hypothetical physical truth, works the other way around – the means justify the ends. The conclusion is less important than the evidence and analysis used to reach it. Therefore, to tell the difference between an honest scientific argument and one that was constructed for political means, one simply has to distinguish between the ends and the means, and decide which is more central to the structure of the argument.

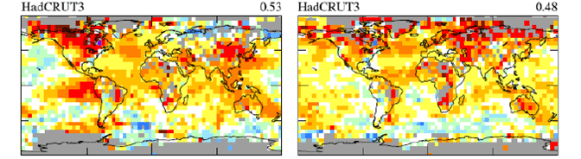

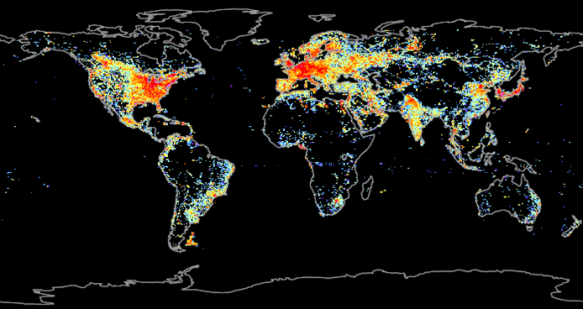

Let us now apply this strategy to the arguments of three of the skeptics who are most visible in the media. In articles from the popular press and news segments from major television stations, the names of these skeptics appear more than any others. Firstly, S. Fred Singer is an atmospheric physicist and retired environmental science professor. He has rarely published in scientific journals since the 1960s, but he is very visible in the media. In the past five years, he has claimed that the Earth has been cooling since 1998 (Avery, 2006), that the Earth is warming, but it is natural and unstoppable (Avery and Singer, 2007), and that the warming is artificial and due to the urban heat island effect (Singer, 2005).

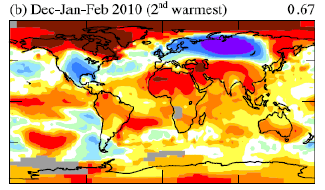

Richard Lindzen, also an atmospheric physicist, is far more active in the scientific community than Singer. However, most of his publications, including the prestigious IPCC report to which he contributed, conclude that climate change is real and caused by humans. His only published theory that disputed climate change was met with vigorous criticism, and he has publicly retracted it, referring to it as “an old view” (Seed Magazine, 2006). Therefore, in his academic life, Lindzen appears to be a mainstream climate scientist – contributing to assessment reports, abandoning theories that are disproved, and publishing work that affirms the theory of anthropogenic climate change. However, when Lindzen talks to the media, his statements change. He has implied that the world is not warming by calling attention to the lack of warming in the Antarctic (Bailey, 2004) and the thickening of some parts of the Greenland ice sheet (Beam, 2006), without explaining that both of these apparent contradictions are well understood by scientists and in no way disprove warming. He has also claimed that the observed warming is minimal and natural (Fox News, 2006).

Finally, Patrick Michaels is an ecological climatologist who occasionally publishes peer-reviewed studies, but none that support his more outlandish claims. In statements to the media, Michaels has said that the observed warming is below what computer models predicted (Chatterjee, 2009), that natural variations in oceanic cycles such as El Niño explain most of the warming (Knappenberger and Michaels, 2009), and that human activity explains most of the warming but it’s nothing to worry about because technology will save us (Miller, 2009).

While examining these arguments from skeptical scientists, something quickly becomes apparent: many of the arguments are contradictory. For example, how can the world be cooling if it is also warming naturally? Not only do the skeptics as a group seem unable to agree on a consistent explanation, some of the individuals either change their mind every year or believe two contradictory theories at the same time. Additionally, none of these arguments are supported by the peer-reviewed literature. They are all elementary misconceptions which were proven erroneous long ago.

With a little bit of research, the claims of these skeptics quickly fall apart. It does not seem possible that they are attempting to capture the attention of other researchers, as their arguments are so weak and inconsistent. However, their pattern of arguments does work as a media strategy, as most people will trust what a scientist says in the newspaper, and not research his reputation or remember his name. Over time, the public will start to remember dozens of so-called problems with the anthropogenic climate change theory. From this perspective, it certainly seems that prominent skeptics are focusing on the ends, rather than the means. They are simply collecting as many arguments as they can to denounce global warming, and publicizing them vigorously. But why?

Earlier, we identified that organizations with a laissez-faire agenda would have reason to spread doubt on climate change, as the most effective form of mitigation would involve government regulation of fossil fuels. Many of these organizations, known as conservative think tanks, exist. Think tanks are supposed to be centres of independent, policy-related research, but conservative think tanks have migrated into an entirely new category. Over the past forty years, they have evolved into lobby groups that denounce any threat to the free market or laissez-faire economics. This objective often leads to the denial of established science, such as the relationship between smoking and cancer (which, if accepted, would lead to government regulation of tobacco and controls on where people could smoke), the destructive effects of CFCs on ozone (which could ban the products of an entire chemical industry), and, most recently, the climatic forcing of fossil fuel combustion, and the attribution of late-20th-century warming to this forcing.

The tactics that conservative think tanks (CTTs) use to manufacture doubt on climate change are often questionable and dishonest. On the rare occasion that their citations are peer-reviewed, they are discredited, cherry-picked, or misrepresented. For example, CTTs repeatedly cite data that shows slight cooling of the Earth – but only from before mechanical flaws in the satellites were corrected and the data began to show warming. They also cite a 2003 study by Sallie Baliunas and Willie Soon, claiming that the recent warming is attributable to sunspots. What CTTs don’t say is that, following the publication of this paper, 13 of the authors of data sets it incorporated refuted Baliunas’ interpretation of their work, and half of the editorial board resigned in protest against failure of the peer-review process. Additionally, CTTs argue that the wavelength band of CO2 absorption is already saturated, so adding more CO2 to the atmosphere wouldn’t cause any more warming – a theory that scientists proved wrong when spectroscopes improved in the 1950s.

Again, note the inconsistency of these statements, all of which were present at the same time on the Heartland Institute’s website. This CTT simultaneously claims that the world is cooling, that the world is warming naturally, and that the world is warming anthropogenically, but has maximized its potential. Evidently, these arguments were chosen because they fit with a preconceived conclusion, not with our understanding of science.

When their arguments are so similar, it should come as no surprise that most skeptics have ties to CTTs. Many of the most prominent skeptics write books – S. Fred Singer has written at least eight books skeptical of climate change, and Patrick Michaels has written at least five (Amazon). In 2008, a survey was conducted of books skeptical of climate change or other environmental issues, and found that an incredible 92% of the authors were affiliated with a CTT (Jacques, Dunlap, and Freeman, 2008). Additionally, some of the authors had connections to more than one CTT. For example, S. Fred Singer has been a part of ten different CTTs throughout his career. Patrick Michaels has been part of two, and Richard Lindzen has been part of three (Greenpeace USA).

It is obvious that CTTs want “experts” on their staff, because they want to sound scientific and credible. Additionally, the CTTs are willing to pay generous sums of money for expertise with a convenient conclusion. In 2006, the American Enterprise Institute offered ten thousand dollars plus expenses to any scientist who wrote a critique of the IPCC (Hoggan and Littlemore, 2009). Sure enough, a handful of scientists responded, and with good reason – they wouldn’t get a ten-thousand-dollar bonus for publishing a regular old peer-reviewed study.

What do these ties with CTTs tell us about skeptics? Have they decided to switch careers from researchers to PR representatives, trading in their scientific integrity for the promise of monetary gain? After all, if they work for a CTT, their arguments don’t have to be accurate – they just have to be effective in manufacturing doubt.

Another interesting fact about publicized skepticism is that it did not appear until governments started promising action on climate change – George HW Bush in 1988 (Hoggan and Littlemore, 2009), Margaret Thatcher in 1990 (Thatcher, 1990), and Brian Mulroney in 1992 (United Nations). In fact, 87% of the books from the Jacques, Dunlap, and Freeman survey were published in or before 1988. Those published before likely did not even mention climate change – many of their titles suggested skepticism about toxic chemicals, the environmental concern of the 1970s. Therefore, it is very easy to pinpoint a short period of years and political events that sparked mass PR coverage of skeptical viewpoints. This trigger provides yet more evidence that skeptics are publicizing their views not to further scientific knowledge, but to manufacture public doubt and delay action.

So, when skepticism started in response to political promises, where were its roots? Unsurprisingly, the manufacture of doubt started with fossil fuel companies. In 1991, the Western Fuel Association, the National Coal Association, and the Edison Electric Institute formed a PR coalition named, ironically, the Information Council on the Environment (ICE). ICE launched a major advertising campaign denouncing the idea of anthropogenic global warming. The campaign’s objective, in ICE’s own words, was “to reposition global warming as a theory (not fact)” and “to supply alternative facts that suggest global warming will be good” (Hoggan and Littlemore, 2009). These objectives are a blatant example of manufacturing doubt, because they are based on the ends, not the means. ICE chose a conclusion that was convenient for their industry, and cherry-picked “alternative facts” to support it.

Several years later, a leaked document from another fossil fuel company, the American Petroleum Institute, gave away the organization’s entire game plan. The document laid out an ideal scenario in which the media reflected climate change as an equal-sided, unsettled debate, citizens began to accept this framing, and public support for the Kyoto Protocol fell apart. To achieve this utopia, API planned to “produce, distribute via syndicate and directly to newspapers nationwide a steady stream of op-ed columns and letters to the editor authored by scientists” (Walker, 1998). By manipulating how the media framed climate change, API could push public opinion in a predetermined direction. This document shows that fossil fuel companies such as the API have stopped caring about science anymore, otherwise the objectives would be “to publish our latest discovery that invalidates global warming in a prestigious journal”. Rather, their efforts are focused on the media, the public, and policymakers. They are consistently promoting ends that don’t have means to support them.

Over the last decade, however, fossil fuels have gradually shifted away from creating their own propaganda, choosing to fund CTTs instead. ExxonMobil, for example, has spent $20 million since 1998 funding CTTs that express climate change skepticism (Hoggan and Littlemore, 2009), and it releases annual breakdowns of its funding. Let’s look at some of the CTTs that our three major skeptics are a part of. Firstly, the Science and Environmental Policy Project, of which S. Fred Singer is president, has received $20 000 from Exxon since 1998. The Cato Institute, which has Patrick Michaels as a senior fellow, Richard Lindzen as a contributing expert, and S. Fred Singer as an advisory board member, has received $125 000. The Heartland Institute, which lists all three as “HeartlandGlobalWarming.org experts”, has received $676 500. (Greenpeace USA). At times, Exxon specifically notes that this funding is for “climate change efforts”, so it’s pretty obvious what kind of message they’re pushing.

Fossil fuel companies are some of the largest businesses in the world, and they are using their money and power to promote messages that are convenient for their further domination. Conservative think tanks – and, therefore, the experts they employ – are being paid, by vested interests, to say that global warming isn’t real. It provides yet another motive for skeptics to give more weight to the ends, rather than the means.

It seems quite obvious that these skeptics should not be trusted, as their arguments are inconsistent and unsupported, and they have potential fortunes resting on what they say, not how they prove it. However, the vested interests of CTTs and fossil fuel companies have been wildly successful in using these skeptics as their spokespeople. For example, the majority of articles from well-respected newspapers present the issue as an equal-sided debate, giving equal time to arguments for and against the idea of human-caused climate change (Boykoff and Boykoff, 2004). This framing has permeated to the public, as 39% of American adults think humans are not changing the climate (Gallup, 2007), and 42% think scientists disagree a lot about the issue (Newsweek, 2007). The constant presence of manufactured doubt in the media has taken its toll.

Additionally, since the skeptical view exploded following the near-action in the late 1980s, our society has spent 20 years without any significant plans for mitigation. The Kyoto Protocol failed in both Canada and the US. The Copenhagen summit did not lead to any politically binding targets. US President Barack Obama is finding it difficult to pass even the most meagre cap-and-trade legislation through the Senate, and the position of the Canadian government is to wait and see what the Americans do.

A democracy cannot function without an electorate that is accurately informed. We see an example of this scenario with regards to climate change legislation. Even though the scientific community is, essentially, as sure as it can get about the existence of human-caused climate change, the manufacture of doubt has prevented the public opinion from following suit, and prevented voters from demanding necessary political action. A well-funded campaign has led us astray from the ideals of democracy.

It’s not over yet, though. Climate change action is not a question of all or nothing. Even if we fail to keep the warming at a tolerable level, there is still a wide range of outcomes. Three degrees of warming is better than five, and five degrees is better than eight. We should never throw up our hands and say that all is lost, because we can always prevent the situation from getting worse.

To pull our society together in order to minimize global warming, we need the public to be better informed about climate change. This does not require everyone to know climate science – rather, all that is needed is for the public to be able to recognize whether or not they can trust an argument. Everyone needs to understand the importance of peer-review and the difference between the ends and the means. People do not need to know science – they just need to know how the system of scientific opinion works. Once this literacy becomes widespread, people will understand the urgency of action, and they will stop listening to those skeptical scientists on the news.

Works Cited

Amazon. “Patrick Michaels.” Amazon.com. Web. 7 Jan. 2010.

Amazon. “S. Fred Singer.” Amazon.com. Web. 7 Jan. 2010.

Bailey, Ronald. “Two Sides to Global Warming.” Weblog post. Reason.com. 10 Nov. 2004. Web. 9 Dec. 2009. <http://reason.com/archives/2004/11/10/two-sides-to-global-warming>.

Beam, Alex. “MIT’s Inconvenient Scientist.” Boston Globe. 30 Aug. 2006. Web. 9 Dec. 2009. <http://www.boston.com/news/globe/living/articles/2006/08/30/mits_inconvenient_scientist>.

Boykoff, Maxwell, and Jules Boykoff. “Balance as bias: global warming and the US prestige press.” Global Environmental Change 14 (2004): 125-36. Print.

Chatterjee, Neera. “Prof. says climate change exaggerated.” The Dartmouth. 24 Feb. 2009. Web. 10 Dec. 2009. <http://thedartmouth.com/2009/02/24/news/climate>.

Dennis, Avery. “Global Cooling?” Web log post. Free Republic. 30 June 2006. Web. 9 Dec. 2009. <http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1658580/posts>.

Doran, Peter, and Maggie Zimmerman. “Examining the Scientific Consensus on Climate Change.” EOS 90.3 (2009): 22-23. Print.

Exxon Secrets. Greenpeace USA. Web. 10 Nov. 2009. <http://www.exxonsecrets.org/maps.php>.

Fox News. “Global Warming: Climate of Fear?” Fox News. 25 May 2006. Web. 9 Dec. 2009. <http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,195551,00.html>.

Gallup. Environment Poll. 2007. Raw data.

Heartland Institute. Heartland Institute. Web. 13 Dec. 2009. <http://heartland.org>.

Hoggan, James, and Richard Littlemore. Climate Cover-Up. Vancouver: Greystone, 2009. Print.

Jacques, Peter, Riley Dunlap, and Mark Freeman. “The organisation of denial: Conservative think tanks and environmental scepticism.” Environmental Politics 17.3 (2008): 349-85. Print.

Kennedy, Donald. “An Unfortunate U-Turn on Carbon.” Science 291.5513 (2001): 2515. Print.

Logical Science. “The Consensus on Global Warming/Climate Change: From Science to Industry & Religion.” Logical Science. 2006. Web. 9 Nov. 2009.

Luntz, Frank. “Straight Talk: The Environment: A Cleaner, Safer, Healthier America.” Letter to Republican Party. 2002. Political Strategy. Web. 10 Nov. 2009. <http://www.politicalstrategy.org/archives/001330.php>.

Miller, Dan. “Look Who’s Talking.” Heartland Institute. 28 May 2009. Web. 10 Dec. 2009.

Miller, Dan. “Look Who’s Talking.” Heartland Institute. 28 May 2009. Web. 10 Dec. 2009.

Newsweek. Environment Poll. 2007. Raw data.

Oreskes, Naomi. “Beyond the Ivory Tower: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change.” Science 306.5702 (2004): 1686. Print.

Oreskes, Naomi. “You CAN Argue with the Facts.” Stanford University. Apr. 2008. Lecture.

Paul, Knappenberger C., and Michaels J. Patrick. “Scientific Shortcomings in the EPA’s Endangerment Finding from Greenhouse Gases.” Cato Journal. Cato Institute, 2009. Web. 9 Dec. 2009. <http://www.cato.org/pubs/journal/cj29n3/cj29n3-8.pdf>.

Revkin, Andrew. “Industry Ignored Its Scientists on Climate.” New York Times. 23 Apr. 2009. Web. 10 Nov. 2009. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/24/science/earth/24deny.html>.

Seed Magazine. “The Contrarian.” SeedMagazine.com. 24 Aug. 2006. Web. 3 Jan. 2010. <http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/the_contrarian/?page=all>.

Singer, S. Fred, and Dennis Avery. Unstoppable Global Warming: Every 1500 Years. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield,, 2007. Print.

Singer, S. Fred. “British Documentary Counters Gore Movie.” Heartland Institute. 1 June 2005. Web. 9 Dec. 2009.

SourceWatch. “Global Climate Coalition.” SourceWatch. Web. 7 Nov. 2009. <http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php?title=Global_Climate_Coalition>.

Thatcher, Margaret. “Speech at 2nd World Climate Conference.” Speech. 2nd World Climate Conference. Geneva. 1990. Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Web. 9 Nov. 2009. <http://www.margaretthatcher.org/speeches/displaydocument.asp?docid=108237>.

United Nations. “Country Profile – Canada.” United Nations. Web. 9 Nov. 2009. <http://www.un.org/esa/earthsummit/cnda-cp.htm>.

Walker, Joe. “Draft Global Climate Science Communications plan.” Letter to Global Climate Science Team. Apr. 1998. Web. 9 Nov. 2009. <http://euronet.nl/users/e_wesker/ew@shell/API-prop.html>.

Weart, Spencer. The Discovery of Global Warming. Harvard UP, 2004. Print.

Several months ago, I wrote a generally favourable review of geophysicist Dr. Henry Pollack’s newest book,

Several months ago, I wrote a generally favourable review of geophysicist Dr. Henry Pollack’s newest book,