Last week at AGU, I presented the results of the project Steve Easterbrook and I worked on this summer. Click the thumbnail on the left for a full size PDF. Also, you can download the updated versions of our software diagrams:

Last week at AGU, I presented the results of the project Steve Easterbrook and I worked on this summer. Click the thumbnail on the left for a full size PDF. Also, you can download the updated versions of our software diagrams:

- COSMOS (COmmunity earth System MOdelS) 1.2.1

- Model E: Oct. 11, 2011 snapshot

- HadGEM3 (Hadley Centre Global Environmental Model, version 3): August 2009 snapshot

- CESM (Community Earth System Model) 1.0.3

- GFDL (Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory), Climate Model 2.1 coupled to MOM (Modular Ocean Model) 4.1

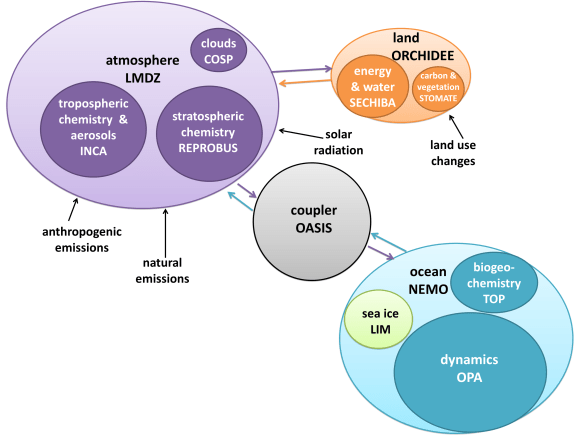

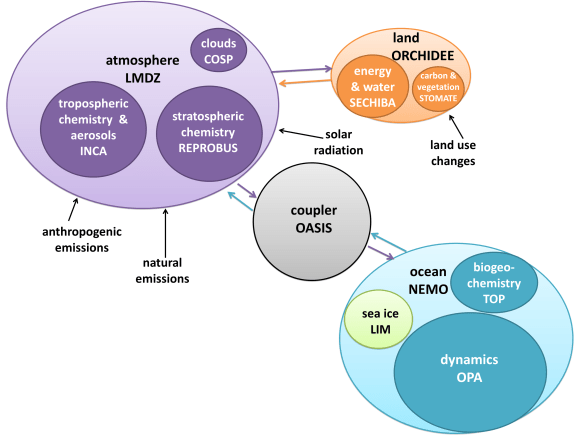

- IPSL (Institut Pierre Simon Laplace), Climate Model 5A

- UVic ESCM (Earth System Climate Model) 2.9

And, since the most important part of poster sessions is the schpiel you give and the conversations you have, here is my schpiel:

Steve and I realized that while comparisons of the output of global climate models are very common (for example, CMIP5: Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5), nobody has really sat down and compared their software structure. We tried to fill this gap in research with a qualitative comparison study of seven models. Six of them are GCMs (General Circulation Models – the most complex climate simulations) in the CMIP5 ensemble; one, the UVic model, is not in CMIP because it’s really more of an EMIC (Earth System Model of Intermediate Complexity – simpler than a GCM). However, it’s one of the most complex EMICs, and contains a full GCM ocean, so we thought it would present an interesting boundary case. (Also, the code was easier to get access to than the corresponding GCM from Environment Canada. When we write this up into a paper we will probably use that model instead.)

I created a diagram of each model’s architecture. The area of each bubble is roughly proportional to the lines of code in that component, which we think is a pretty good proxy for complexity – a more complex model will have more subroutines and functions than a simple one. The bubbles are to scale within each model, but not between models, as the total lines of code in a model varies by about a factor of 10. A bit difficult to fit on a poster and still make everything readable! Fluxes from each component are represented by coloured arrows (the same colour as the bubble), and often pass through the coupler before reaching another component.

I created a diagram of each model’s architecture. The area of each bubble is roughly proportional to the lines of code in that component, which we think is a pretty good proxy for complexity – a more complex model will have more subroutines and functions than a simple one. The bubbles are to scale within each model, but not between models, as the total lines of code in a model varies by about a factor of 10. A bit difficult to fit on a poster and still make everything readable! Fluxes from each component are represented by coloured arrows (the same colour as the bubble), and often pass through the coupler before reaching another component.

We examined the amount of encapsulation of components, which varies widely between models. CESM, on one end of the spectrum, isolates every component completely, particularly in the directory structure. Model E, on the other hand, places nearly all of its files in the same directory, and has a much higher level of integration between components. This is more difficult for a user to read, but it has benefits for data transfer.

While component encapsulation is attractive from a software engineering perspective, it poses problems because the real world is not so encapsulated. Perhaps the best example of this is sea ice. It floats on the ocean, its extent changing continuously. It breaks up into separate chunks and can form slush with the seawater. How do you split up ocean code and ice code? CESM keeps the two components completely separate, with a transient boundary between them. IPSL represents ice as an encapsulated sub-component of their ocean model, NEMO (Nucleus for European Modeling of the Ocean). COSMOS integrates both ocean and ice code together in MPI-OM (Max Planck Institute Ocean Model).

GFDL took a completely different, and rather innovative, approach. Sea ice in the GFDL model is an interface, a layer over the ocean with boolean flags in each cell indicating whether or not ice is present. All fluxes to and from the ocean must pass through the “sea ice”, even if they’re at the equator and the interface is empty.

Encapsulation requires code to tie components together, since the climate system is so interconnected. Every model has a coupler, which fulfills two main functions: controlling the main time-stepping loop, and passing data between components. Some models, such as CESM, use the coupler for every interaction. However, if two components have the same grid, no interpolation is necessary, so it’s often simpler just to pass them directly. Sometimes this means a component can be completely disconnected from the coupler, such as the land model in IPSL; other times it still uses the coupler for other interactions, such as the HadGEM3 arrangement with direct ocean-ice fluxes but coupler-controlled ocean-atmosphere and ice-atmosphere fluxes.

While it’s easy to see that some models are more complex than others, it’s also interesting to look at the distribution of complexity within a model. Often the bulk of the code is concentrated in one component, due to historical software development as well as the institution’s conscious goals. Most of the models are atmosphere-centric, since they were created in the 1970s when numerical weather prediction was the focus of the Earth system modelling community. Weather models require a very complex atmosphere but not a lot else, so atmospheric routines dominated the code. Over time, other components were added, but the atmosphere remained at the heart of the models. The most extreme example is HadGEM3, which actually uses the same atmosphere model for both weather prediction and climate simulations!

The UVic model is quite different. The University of Victoria is on the west coast of Canada, and does a lot of ocean studies, so the model began as a branch of the MOM ocean model from GFDL. The developers could have coupled it to a complex atmosphere model in an effort to mimic full GCMs, but they consciously chose not to. Atmospheric routines need very short time steps, so they eat up most of the run time, and make very long simulations not feasible. In an effort to keep their model fast, UVic created EMBM (Energy Moisture Balance Model), an extremely simple atmospheric model (for example, it doesn’t include dynamic precipitation – it simply rains as soon as a certain humidity is reached). Since the ocean is the primary moderator of climate over the long run, the UVic ESCM still outputs global long-term averages that match up nicely with GCM results.

Finally, CESM and Model E could not be described as “land-centric”, but land is definitely catching up – it’s even surpassed the ocean model in both cases! These two GCMs are cutting-edge in terms of carbon cycle feedbacks, which are primarily terrestrial, and likely very important in determining how much warming we can expect in the centuries to come. They are currently poorly understood and difficult to model, so they are a new frontier for Earth system modelling. Scientists are moving away from a binary atmosphere-ocean paradigm and towards a more comprehensive climate system representation.

I presented this work to some computer scientists in the summer, and many of them asked, “Why do you need so many models? Wouldn’t it be better to just have one really good one that everyone collaborated on?” It might be simpler from a software engineering perspective, but for the purposes of science, a variety of diverse models is actually better. It means you can pick and choose which model suits your experiment. Additionally, it increases our confidence in climate model output, because if dozens of independent models are saying the same thing, they’re more likely to be accurate than if just one model made a given prediction. Diversity in model architecture arguably produces the software engineering equivalent of perturbed physics, although it’s not systematic or deliberate.

A common question people asked me at AGU was, “Which model do you think is the best?” This question is impossible to answer, because it depends on how you define “best”, which depends on what experiment you are running. Are you looking at short-term, regional impacts at a high resolution? HadGEM3 would be a good bet. Do you want to know what the world will be like in the year 5000? Go for UVic, otherwise you will run out of supercomputer time! Are you studying feedbacks, perhaps the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum? A good choice would be CESM. So you see, every model is the best at something, and no model can be the best at everything.

You might think the ideal climate model would mimic the real world perfectly. It would still have discrete grid cells and time steps, but it would be like a digital photo, where the pixels are so small that it looks continuous even when you zoom in. It would contain every single Earth system process known to science, and would represent their connections and interactions perfectly.

Such a model would also be a nightmare to use and develop. It would run slower than real time, making predictions of the future useless. The code would not be encapsulated, so organizing teams of programmers to work on certain aspects of the model would be nearly impossible. It would use more memory than computer hardware offers us – despite the speed of computers these days, they’re still too slow for many scientific models!

We need to balance complexity with feasibility. A hierarchy of complexity is important, as is a variety of models to choose from. Perfectly reproducing the system we’re trying to model actually isn’t the ultimate goal.

Please leave your questions below, and hopefully we can start a conversation – sort of a virtual poster session!

I created a diagram of each model’s architecture. The area of each bubble is roughly proportional to the lines of code in that component, which we think is a pretty good proxy for complexity – a more complex model will have more subroutines and functions than a simple one. The bubbles are to scale within each model, but not between models, as the total lines of code in a model varies by about a factor of 10. A bit difficult to fit on a poster and still make everything readable! Fluxes from each component are represented by coloured arrows (the same colour as the bubble), and often pass through the coupler before reaching another component.

I created a diagram of each model’s architecture. The area of each bubble is roughly proportional to the lines of code in that component, which we think is a pretty good proxy for complexity – a more complex model will have more subroutines and functions than a simple one. The bubbles are to scale within each model, but not between models, as the total lines of code in a model varies by about a factor of 10. A bit difficult to fit on a poster and still make everything readable! Fluxes from each component are represented by coloured arrows (the same colour as the bubble), and often pass through the coupler before reaching another component. I know that many of you will be at the annual American Geophysical Union conference next week in San Francisco. If so, I’d invite you to come by and take a look at our poster! It will be up all Thursday morning in Halls A-C, Moscone South. I will be around for at least part of the morning to chat and answer questions.

I know that many of you will be at the annual American Geophysical Union conference next week in San Francisco. If so, I’d invite you to come by and take a look at our poster! It will be up all Thursday morning in Halls A-C, Moscone South. I will be around for at least part of the morning to chat and answer questions.