“It is remarkable and untenable that the second largest forcing

that drives global climate change remains unmeasured,” writes Dr. James Hansen, the head of NASA’s climate change research team, and arguably the world’s top climatologist.

The word “forcing” refers to a factor, such as changes in the Sun’s output or in atmospheric composition, that exerts a warming or cooling influence on the Earth’s climate. The climate doesn’t magically change for no reason – it is always driven by something. Scientists measure these forcings in Watts per square metre – imagine a Christmas tree lightbulb over every square metre of the Earth’s surface, and you have 1 W/m2 of positive forcing.

Currently, the largest forcing on the Earth’s climate is that of increasing greenhouse gases from burning fossil fuels. These exert a positive, or warming, forcing, hence the term “global warming”. However, a portion of this positive forcing is being cancelled out by the second-largest forcing, which is also anthropogenic. Many forms of air pollution, collectively known as aerosols, exert a negative (cooling) forcing on the Earth’s climate. They do this in two ways: the direct albedo effect (scattering solar radiation so it never reaches the planet), and the indirect albedo effect (providing surfaces for clouds to form and scatter radiation by themselves). A large positive forcing and a medium negative forcing sums out to a moderate increase in global temperatures.

Unfortunately, a catch-22 exists with aerosols. As many aerosols are directly harmful to human health, the world is beginning to regulate them through legislation such as the American Clean Air Act. As this pollution decreases, its detrimental health effects will lessen, but so will its ability to partially cancel out global warming.

The problem is that we don’t know how much warming the aerosols are cancelling – that is, we don’t know the magnitude of the forcing. So, if all air pollution ceased tomorrow, the world could experience a small jump in net forcing, or a large jump. Global warming would suddenly become much worse, but we don’t know just how much.

The forcing from greenhouse gases is known with a high degree of accuracy – it’s just under 3 W/m2. However, all we know about aerosol forcing is that it’s somewhere around -1 or -2 W/m2 – an estimate is the best we can do. The reason for this dichotomy lies in the ease of measurement. Greenhouse gases last a long time (on the order of centuries) in the atmosphere, and mix through the air, moving towards a uniform concentration. An air sample from a remote area of the world, such as Antarctica or parts of Hawaii, will be uncontaminated by cars and factories nearby, and will contain an accurate value of the global atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration (the same can be done for other greenhouse gases, such as methane) . From these measurements, molecular physics can tell us how large the forcing is. Direct records of carbon dioxide concentrations have been kept since the late 1950s:

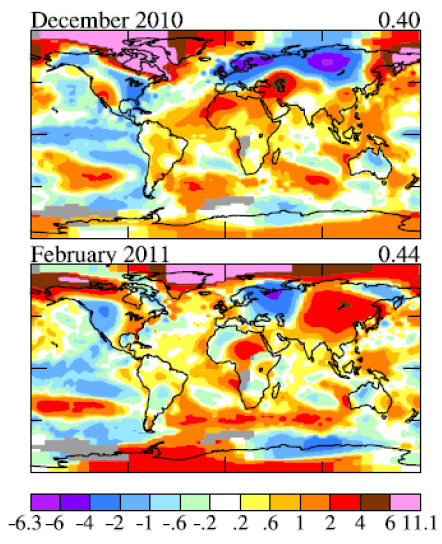

However, aerosols only stay in the troposphere for a few days, as precipitation washes them out of the air. For this reason, they don’t have time to disperse evenly, and measurements are not so simple. The only way to gain accurate measurements of their concentrations is with a satellite. NASA recently launched the Glory satellite for just this purpose. Unfortunately, it failed to reach orbit (an inherent risk for satellites), and given the current political climate in the United States, it seems overly optimistic to hope for funding for a new one any time soon. Luckily, if this project was carried out by the private sector, without the need for money-draining government review panels, James Hansen estimates that it could be achieved with a budget of around $100 million.

An accurate value for aerosol forcing can only be achieved with accurate measurements of aerosol concentration. Knowing this forcing would be immensely helpful for climate researchers, as it impacts not only the amount of warming we can expect, but also how long it will take to play out, until the planet reaches thermal equilibrium. Aimed with better knowledge of these details will allow policymakers to better plan for the future, regarding both mitigation of and adaptation to climate change. Finally measuring the impact of aerosols, instead of just estimating, could give our understanding of the climate system the biggest bang for its buck.