Also published at Skeptical Science

This is a climate model:

T = [(1-α)S/(4εσ)]1/4

(T is temperature, α is the albedo, S is the incoming solar radiation, ε is the emissivity, and σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant)

An extremely simplified climate model, that is. It’s one line long, and is at the heart of every computer model of global warming. Using basic thermodynamics, it calculates the temperature of the Earth based on incoming sunlight and the reflectivity of the surface. The model is zero-dimensional, treating the Earth as a point mass at a fixed time. It doesn’t consider the greenhouse effect, ocean currents, nutrient cycles, volcanoes, or pollution.

If you fix these deficiencies, the model becomes more and more complex. You have to derive many variables from physical laws, and use empirical data to approximate certain values. You have to repeat the calculations over and over for different parts of the Earth. Eventually the model is too complex to solve using pencil, paper and a pocket calculator. It’s necessary to program the equations into a computer, and that’s what climate scientists have been doing ever since computers were invented.

A pixellated Earth

Today’s most sophisticated climate models are called GCMs, which stands for General Circulation Model or Global Climate Model, depending on who you talk to. On average, they are about 500 000 lines of computer code long, and mainly written in Fortran, a scientific programming language. Despite the huge jump in complexity, GCMs have much in common with the one-line climate model above: they’re just a lot of basic physics equations put together.

Computers are great for doing a lot of calculations very quickly, but they have a disadvantage: computers are discrete, while the real world is continuous. To understand the term “discrete”, think about a digital photo. It’s composed of a finite number of pixels, which you can see if you zoom in far enough. The existence of these indivisible pixels, with clear boundaries between them, makes digital photos discrete. But the real world doesn’t work this way. If you look at the subject of your photo with your own eyes, it’s not pixellated, no matter how close you get – even if you look at it through a microscope. The real world is continuous (unless you’re working at the quantum level!)

Similarly, the surface of the world isn’t actually split up into three-dimensional cells (you can think of them as cubes, even though they’re usually wedge-shaped) where every climate variable – temperature, pressure, precipitation, clouds – is exactly the same everywhere in that cell. Unfortunately, that’s how scientists have to represent the world in climate models, because that’s the only way computers work. The same strategy is used for the fourth dimension, time, with discrete “timesteps” in the model, indicating how often calculations are repeated.

It would be fine if the cells could be really tiny – like a high-resolution digital photo that looks continuous even though it’s discrete – but doing calculations on cells that small would take so much computer power that the model would run slower than real time. As it is, the cubes are on the order of 100 km wide in most GCMs, and timesteps are on the order of hours to minutes, depending on the calculation. That might seem huge, but it’s about as good as you can get on today’s supercomputers. Remember that doubling the resolution of the model won’t just double the running time – instead, the running time will increase by a factor of sixteen (one doubling for each dimension).

Despite the seemingly enormous computer power available to us today, GCMs have always been limited by it. In fact, early computers were developed, in large part, to facilitate atmospheric models for weather and climate prediction.

Cracking the code

A climate model is actually a collection of models – typically an atmosphere model, an ocean model, a land model, and a sea ice model. Some GCMs split up the sub-models (let’s call them components) a bit differently, but that’s the most common arrangement.

Each component represents a staggering amount of complex, specialized processes. Here are just a few examples from the Community Earth System Model, developed at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado:

- Atmosphere: sea salt suspended in the air, three-dimensional wind velocity, the wavelengths of incoming sunlight

- Ocean: phytoplankton, the iron cycle, the movement of tides

- Land: soil hydrology, forest fires, air conditioning in cities

- Sea Ice: pollution trapped within the ice, melt ponds, the age of different parts of the ice

Each component is developed independently, and as a result, they are highly encapsulated (bundled separately in the source code). However, the real world is not encapsulated – the land and ocean and air are very interconnected. Some central code is necessary to tie everything together. This piece of code is called the coupler, and it has two main purposes:

- Pass data between the components. This can get complicated if the components don’t all use the same grid (system of splitting the Earth up into cells).

- Control the main loop, or “time stepping loop”, which tells the components to perform their calculations in a certain order, once per time step.

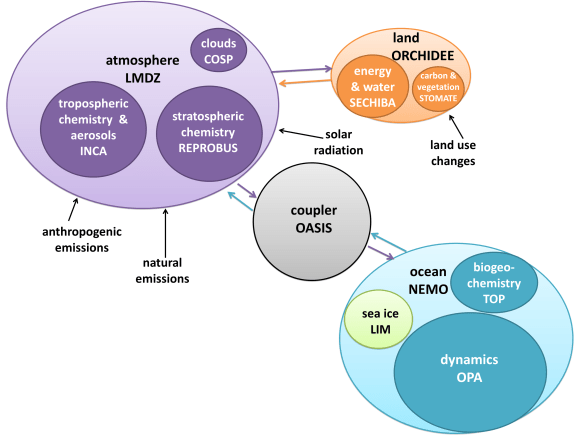

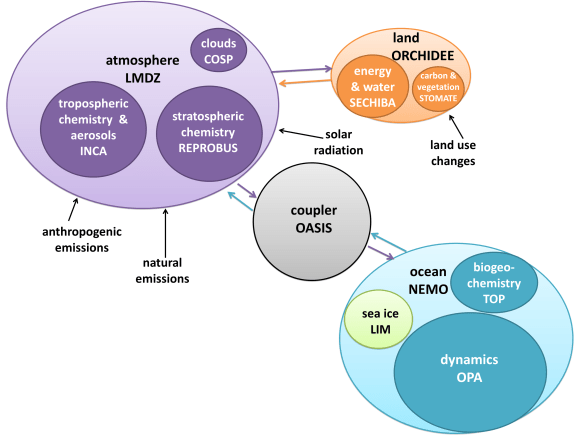

For example, take a look at the IPSL (Institut Pierre Simon Laplace) climate model architecture. In the diagram below, each bubble represents an encapsulated piece of code, and the number of lines in this code is roughly proportional to the bubble’s area. Arrows represent data transfer, and the colour of each arrow shows where the data originated:

We can see that IPSL’s major components are atmosphere, land, and ocean (which also contains sea ice). The atmosphere is the most complex model, and land is the least. While both the atmosphere and the ocean use the coupler for data transfer, the land model does not – it’s simpler just to connect it directly to the atmosphere, since it uses the same grid, and doesn’t have to share much data with any other component. Land-ocean interactions are limited to surface runoff and coastal erosion, which are passed through the atmosphere in this model.

You can see diagrams like this for seven different GCMs, as well as a comparison of their different approaches to software architecture, in this summary of my research.

Show time

When it’s time to run the model, you might expect that scientists initialize the components with data collected from the real world. Actually, it’s more convenient to “spin up” the model: start with a dark, stationary Earth, turn the Sun on, start the Earth spinning, and wait until the atmosphere and ocean settle down into equilibrium. The resulting data fits perfectly into the cells, and matches up really nicely with observations. It fits within the bounds of the real climate, and could easily pass for real weather.

Scientists feed input files into the model, which contain the values of certain parameters, particularly agents that can cause climate change. These include the concentration of greenhouse gases, the intensity of sunlight, the amount of deforestation, and volcanoes that should erupt during the simulation. It’s also possible to give the model a different map to change the arrangement of continents. Through these input files, it’s possible to recreate the climate from just about any period of the Earth’s lifespan: the Jurassic Period, the last Ice Age, the present day…and even what the future might look like, depending on what we do (or don’t do) about global warming.

The highest resolution GCMs, on the fastest supercomputers, can simulate about 1 year for every day of real time. If you’re willing to sacrifice some complexity and go down to a lower resolution, you can speed things up considerably, and simulate millennia of climate change in a reasonable amount of time. For this reason, it’s useful to have a hierarchy of climate models with varying degrees of complexity.

As the model runs, every cell outputs the values of different variables (such as atmospheric pressure, ocean salinity, or forest cover) into a file, once per time step. The model can average these variables based on space and time, and calculate changes in the data. When the model is finished running, visualization software converts the rows and columns of numbers into more digestible maps and graphs. For example, this model output shows temperature change over the next century, depending on how many greenhouse gases we emit:

Predicting the past

So how do we know the models are working? Should we trust the predictions they make for the future? It’s not reasonable to wait for a hundred years to see if the predictions come true, so scientists have come up with a different test: tell the models to predict the past. For example, give the model the observed conditions of the year 1900, run it forward to 2000, and see if the climate it recreates matches up with observations from the real world.

This 20th-century run is one of many standard tests to verify that a GCM can accurately mimic the real world. It’s also common to recreate the last ice age, and compare the output to data from ice cores. While GCMs can travel even further back in time – for example, to recreate the climate that dinosaurs experienced – proxy data is so sparse and uncertain that you can’t really test these simulations. In fact, much of the scientific knowledge about pre-Ice Age climates actually comes from models!

Climate models aren’t perfect, but they are doing remarkably well. They pass the tests of predicting the past, and go even further. For example, scientists don’t know what causes El Niño, a phenomenon in the Pacific Ocean that affects weather worldwide. There are some hypotheses on what oceanic conditions can lead to an El Niño event, but nobody knows what the actual trigger is. Consequently, there’s no way to program El Niños into a GCM. But they show up anyway – the models spontaneously generate their own El Niños, somehow using the basic principles of fluid dynamics to simulate a phenomenon that remains fundamentally mysterious to us.

In some areas, the models are having trouble. Certain wind currents are notoriously difficult to simulate, and calculating regional climates requires an unaffordably high resolution. Phenomena that scientists can’t yet quantify, like the processes by which glaciers melt, or the self-reinforcing cycles of thawing permafrost, are also poorly represented. However, not knowing everything about the climate doesn’t mean scientists know nothing. Incomplete knowledge does not imply nonexistent knowledge – you don’t need to understand calculus to be able to say with confidence that 9 x 3 = 27.

Also, history has shown us that when climate models make mistakes, they tend to be too stable, and underestimate the potential for abrupt changes. Take the Arctic sea ice: just a few years ago, GCMs were predicting it would completely melt around 2100. Now, the estimate has been revised to 2030, as the ice melts faster than anyone anticipated:

Answering the big questions

At the end of the day, GCMs are the best prediction tools we have. If they all agree on an outcome, it would be silly to bet against them. However, the big questions, like “Is human activity warming the planet?”, don’t even require a model. The only things you need to answer those questions are a few fundamental physics and chemistry equations that we’ve known for over a century.

You could take climate models right out of the picture, and the answer wouldn’t change. Scientists would still be telling us that the Earth is warming, humans are causing it, and the consequences will likely be severe – unless we take action to stop it.