Next week, I will be giving a speech on climate change to the green committee of a local United Church. They are particularly interested in science and solutions, so I wrote the following script, drawing heavily from my previous presentations. I would really appreciate feedback and suggestions for this presentation.

Citations will be on the slides (which I haven’t made yet), so they’re not in the text of this script. Let me know if there’s a particular reference you’re wondering about, but they’re probably common knowledge within this community by now.

Enjoy!

Climate change is depressing. I know that really well, because I’ve been studying it for over two years. I’m quite practiced at keeping the scary stuff contained in the analytical part of my brain, and not thinking of the implications – because the implications make you feel powerless. I’m sure that all of us here wish we could stop global warming on our own. So we work hard to reduce our carbon footprints, and then we feel guilty every time we take the car out or buy something that was made in China or turn up the heat a degree.

The truth is, though, the infrastructure of our society doesn’t support a low-carbon lifestyle. Look at the quality of public transit in Winnipeg, or the price of local food. We can work all we want at changing our practices, but it’s an uphill battle. If we change the infrastructure, though – if we put a price on carbon so that sustainable practices are cheaper and easier than using fossil fuels – people everywhere will subsequently change their practices.

Currently, governments – particularly in North America – aren’t too interested in sustainable infrastructure, because they don’t think people care. Politicians only say what they think people want to hear. So, should we go dress up as polar bears and protest in front of Parliament to show them we care? That might work, but they will probably just see us as crazy environmentalists, a fringe group. We need a critical mass of people that care about climate change, understand the problem, and want to fix it. An effective solution requires top-down organization, but that won’t happen until there’s a bottom-up, grassroots movement of people who care.

I believe that the most effective action one person can take in the fight against global warming is to talk to others and educate others. I believe most people are good, and sane, and reasonable. They do the best they can, given their level of awareness. If we increase that awareness, we’ll gain political will for a solution. And so, in an effort to practice what I preach, I’m going to talk to you about the issue.

The science that led us to the modern concern about climate change began all the way back in 1824, when a man named Joseph Fourier discovered the greenhouse effect. Gases such as carbon dioxide make up less than one percent of the Earth’s atmosphere, but they trap enough heat to keep the Earth over 30 degrees Celsius warmer than it would be otherwise.

Without greenhouse gases, there could be no life on Earth, so they’re a very good thing – until their concentration changes. If you double the amount of CO2 in the air, the planet will warm, on average, somewhere around 3 degrees. The first person to realize that humans could cause this kind of a change, through the burning of fossil fuels releasing CO2, was Svante Arrhenius, in 1897. So this is not a new theory by any means.

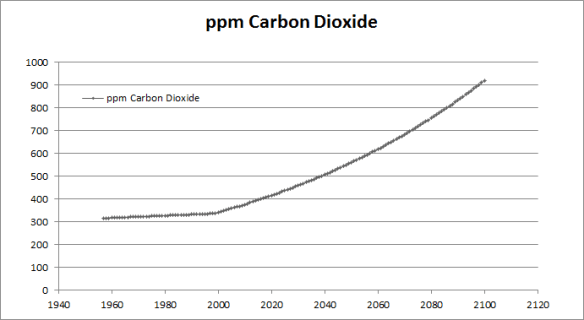

For a long time, scientists assumed that any CO2 we emitted would just get absorbed by the oceans. In 1957, Roger Revelle showed that wasn’t true. The very next year, Charles Keeling decided to test this out, and started measuring the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere. Now, Arrhenius had assumed that it would take thousands of years to double CO2 from the preindustrial value of 280 ppm (which we know from ice cores), but the way we’re going, we’ll get there in just a few decades. We’ve already reached 390 ppm. That might not seem like a lot, but 390 ppm of arsenic in your coffee would kill you. Small changes can have big effects.

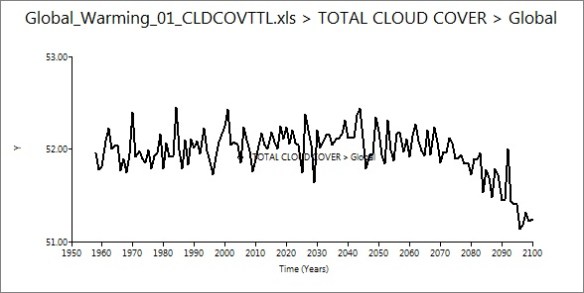

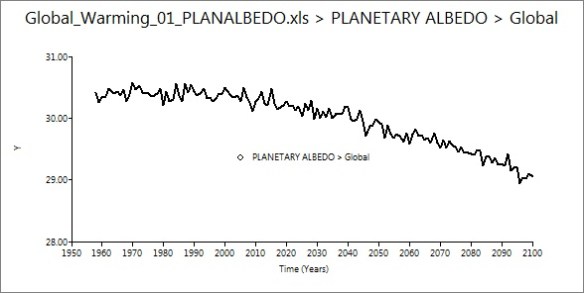

Around the 1970s, scientists realized that people were exerting another influence on the climate. Many forms of air pollution, known as aerosols, have a cooling effect on the planet. In the 70s, the warming from greenhouse gases and the cooling from aerosols were cancelling each other out, and scientists were split as to which way it would go. There was one paper, by Stephen Schneider, which even said it could be possible to cause an ice age, if we put out enough aerosols and greenhouse gases stayed constant. However, as climate models improved, and governments started to regulate air pollution, a scientific consensus emerged that greenhouse gases would win out. Global warming was coming – it was just a question of when.

In 1988, James Hansen, who is arguably the top climate scientist in the world today, claimed it had arrived. In a famous testimony to the U.S. Congress, he said that “the greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now.” Many scientists weren’t so sure, and thought it was too early to make such a bold statement, but Hansen turned out to be right. Since about 1975, the world has been warming, more quickly than it has for at least the last 55 million years.

Over the past decade, scientists have even been able to rule out the possibility that the warming is caused by something else, like a natural cycle. Different causes of climate change have slightly different effects – like the pattern of warming in different layers of the atmosphere, the amount of warming in summer compared to winter, or at night compared to in the day, and so on. Ben Santer pioneered attribution studies: examining these effects in order to pinpoint a specific cause. And so far, nobody has been able to explain how the recent warming could not be caused by us.

Today, there is a remarkable amount of scientific agreement surrounding this issue. Between 97 and 98% of climate scientists, virtually 100% of peer-reviewed studies, and every scientific organization in the world agree that humans are causing the Earth to warm. The evidence for climate change is not a house of cards, where you take one piece out and the whole theory falls apart. It’s more like a mountain. Scrape a handful of pebbles off the top, but the mountain is still there.

However, if you take a step outside of the academic community, this convergence of evidence is more or less invisible. The majority of newspaper articles, from respected outlets like the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal, spend at least as much time arguing against this consensus as they do arguing for it. They present ideas such as “maybe it’s a natural cycle” or “CO2 has no effect on climate” that scientists disproved years ago. The media is stuck in the past. Some of them are only stuck in the 1980s, but others are stuck all the way back in 1800. Why is it like this?

Part of it comes from good, but misguided, intentions. When it comes to climate change, most journalists follow the rule of balance: presenting “two equal sides”, staying neutral, letting the reader form their own opinion. This works well when the so-called controversy is one of political or social nature, like tax levels or capital punishment. In these cases, there is no right answer, and people are usually split into two camps. But when the question at hand is one of science, there is a right answer – even if we haven’t found it yet – so some explanations are better than others, and some can be totally wrong. Would you let somebody form their own opinion on Newton’s Laws of Motion or the reality of photosynthesis? Sometimes scientists are split into two equal groups, but sometimes they’re split into three or four or even a dozen. How do you represent that as two equal sides? Sometimes, like we see with climate change, pretty much all the scientists are in agreement, and the two or three percent which aren’t don’t really publish, because they can’t back up their statements and nobody really takes them seriously. So framing these two groups as having equal weight in the scientific community is completely incorrect. It exaggerates the extreme minority, and suppresses everyone else. Being objective is not always the same as being neutral, and it’s particularly important to remember that when our future is at stake.

Another reason to frame climate science as controversial is that it makes for a much better story. Who really wants to read about scientists agreeing on everything? Journalists try to write stories that are exciting. Unfortunately, that goal can begin to overshadow accuracy.

Also, there are fewer journalists than there used to be, and there are almost no science journalists in the mainstream media – general reporters cover science issues instead. Also, a few decades ago, journalists used to get a week or two to write a story. Now they often have less than a day, because speed and availability of news has become more important than quality.

However, perhaps the most important – and disturbing – explanation for this inaccurate framing is that the media has been very compliant in spreading the message of climate change deniers. They call themselves skeptics, but I don’t think that’s accurate. A true skeptic will only accept a claim given sufficient evidence. That’s a good thing, and all scientists should be skeptics. But it’s easy to see that these people will never accept human-caused climate change, no matter what the evidence. At the same time, they blindly accept any shred of information that seems to support their cause, without applying any skepticism at all. That’s denial, so let’s not compliment them by calling them skeptics.

Climate change deniers will use whatever they can get – whether or not it’s legitimate, whether or not it’s honest – as proof that climate change is natural, or nonexistent, or a global conspiracy. They’ll tell you that volcanoes emit more CO2 than humans, but volcanoes actually emit about 1% of what we do. They’ll say that global warming has stopped because 2008 was cooler than 2007. If climatologists organize a public lecture in effort to communicate accurate scientific information, they’ll say that scientists are dogmatic and subscribe to censorship and will not allow any other opinions to be considered.

Some of these questionable sources are organizations, like a dozen or so lobby groups that have been paid a lot of money by oil companies to say that global warming is fake. Some of them are individuals, like US Senator James Inhofe, who was the environment chair under George W. Bush, and says that “global warming is the greatest hoax ever imposed upon the American people.” Some of them have financial motivations, and some of them have ideological motivations, but their motivations don’t really matter – all that matters is that they are saying things that are inaccurate, and misleading, and just plain wrong.

There has been a recent, and very disturbing, new tactic of deniers. Instead of attacking the science, they’ve begun to attack the integrity of individual scientists. In November 2009, they stole thirteen years of emails from a top climate research group in the UK, and spread stories all over the media that said scientists were caught fudging their data and censoring critics. Since then, they’ve been cleared of these charges by eight independent investigations, but you wouldn’t know it by reading the newspaper. For months, nearly every media outlet in the developed world spread what was, essentially, libel, and the only one that has formally apologized for its inaccurate coverage is the BBC.

In the meantime, there has been tremendous personal impact on the scientists involved. Many of them have received death threats, and Phil Jones, the director of the research group, was nearly driven to suicide. Another scientist, who wishes to remain anonymous, had a dead animal dumped on his doorstep and now travels with bodyguards. The Republican Party, which prides itself on fiscal responsibility, is pushing for more and more investigations, because they just can’t accept that the scientists are innocent…and James Inhofe, the “global warming is a hoax” guy, attempted to criminally prosecute seventeen researchers, most of whom had done nothing but occasionally correspond with the scientists who had their emails stolen. It’s McCarthyism all over again.

So this is where we are. Where are we going?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, which collects and summarizes all the scientific literature about climate change, said in 2007 that under a business-as-usual scenario, where we keep going the way we’re going, the world will warm somewhere around 4 degrees Celsius by 2100. Unfortunately, this report was out of date almost as soon as it was published, and has widely been criticized for being too conservative. The British Meteorological Office published an updated figure in 2009 that estimated we will reach 4 degrees by the 2070s.

I will still be alive then (I hope!). I will likely have kids and even grandkids by then. I’ve spent a lot of time researching climate change, and the prospect of a 4 degree rise is terrifying to me. At 4 degrees, we will have lost control of the climate – even if we stop emitting greenhouse gases, positive feedbacks in the climate system will make sure the warming continues. We will have committed somewhere between 40 and 70 percent of the world’s species to extinction. Prehistoric records indicate that we can expect 40 to 80 metres of eventual sea level rise – it will take thousands of years to get there, but many coastal cities will be swamped within the first century. Countries – maybe even developed countries – will be at war over food and water. All this…within my lifetime.

And look at our current response. We seem to be spending more time attacking the scientists who discovered the problem than we are negotiating policy to fix it. We should have started reducing our greenhouse gas emissions twenty years ago, but if we start now, and work really hard, we do have a shot at stopping the warming at a point where we stay in control. Technically, we can do it. It’s going to take an unprecedented amount of political will and international communication

Everybody wants to know, “What can I do?” to fix the problem. Now, magazines everywhere are happy to tell you “10 easy ways to reduce your carbon footprint” – ride your bike, and compost, and buy organic spinach. That’s not really going to help. Say that enough people reduce their demand on fossil fuels: supply and demand dictates that the price will go down, and someone else will say, “Hey, gas is cheap!” and use more of it. Grassroots sentiment isn’t going to be enough. We need a price on carbon, whether it’s a carbon tax or cap-and-trade…but governments won’t do that until a critical mass of people demand it.

So what can you do? You can work on achieving that critical mass. Engage the apathetic. Educate people. Talk to them about climate change – it’s scary stuff, but suck it up. We’re all going to need to face it. Help them to understand and care about the problem. Don’t worry about the crazy people who shout about socialist conspiracies, they’re not worth your time. They’re very loud, but there’s not really very many of them. And in the end, we all get one vote.